This article covers

What are corals?

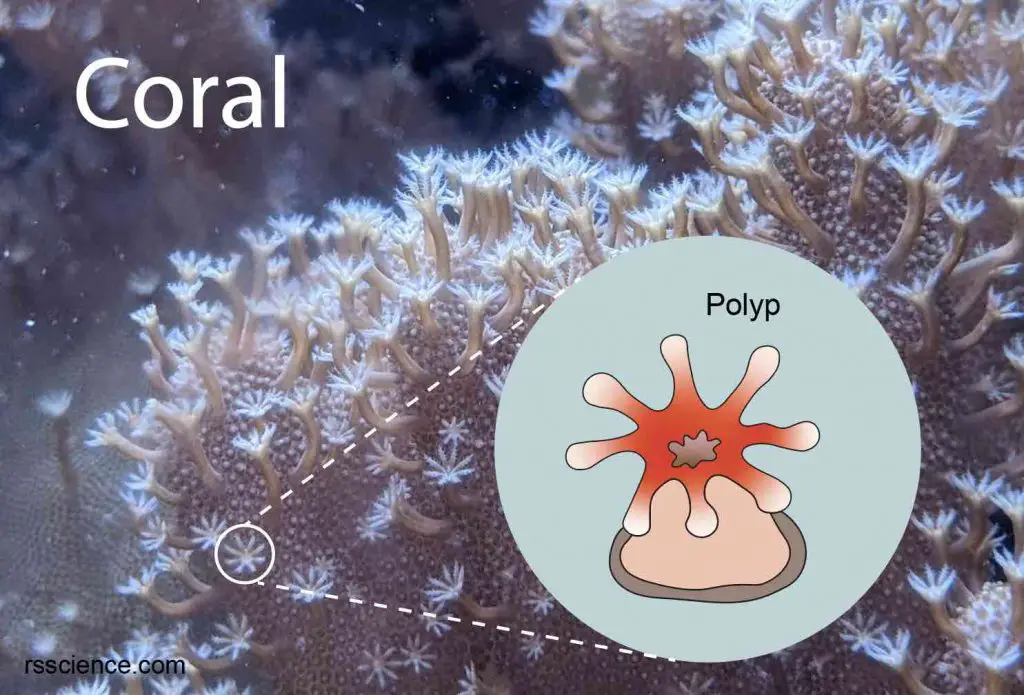

Corals are marine animals that resemble miniature sea anemones. They are misunderstood as plants because they don’t move much and they look like trees. People also think that a whole coral colony is an individual organism. In fact, most of the coral colonies are comprised of many small soft, jelly-like bodies of individual animals, called, polyps. Only small species live as solitary individuals.

[In this image] Illustration of the coral morphology.

(A) Polyp of the solitary coral Flabellum sp, (B) A colony comprised of many individual polyps (finger leather coral), (C) Illustration of single solitary polyp, (D) Illustration of polyps forming a colony.

Photo credit: (A) wiki commons; (B) Tidal gardens

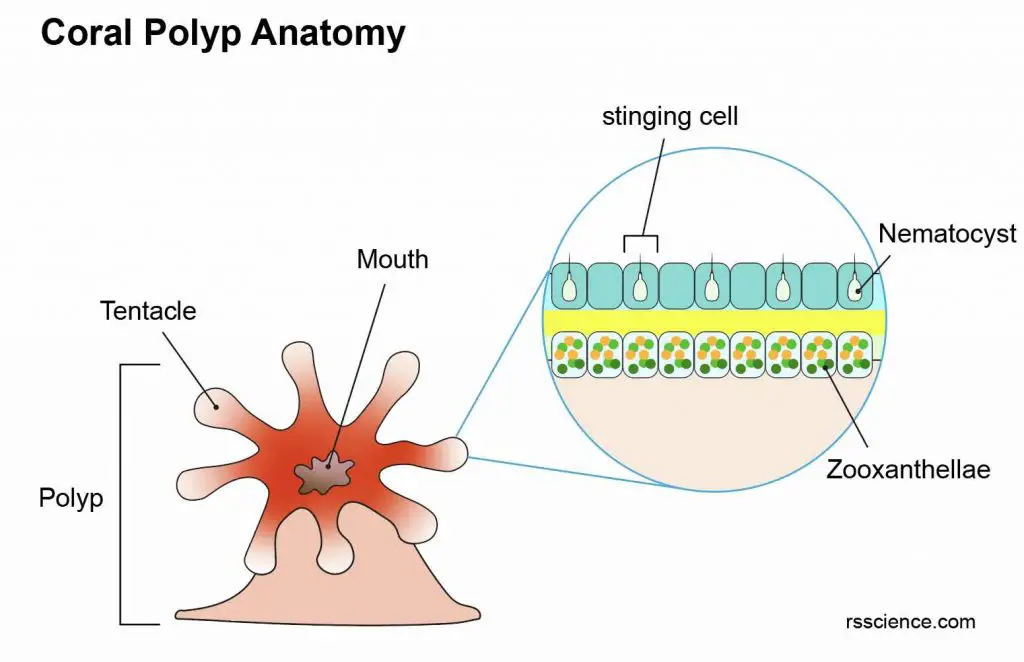

Classification of coral – the Phylum Cnidaria

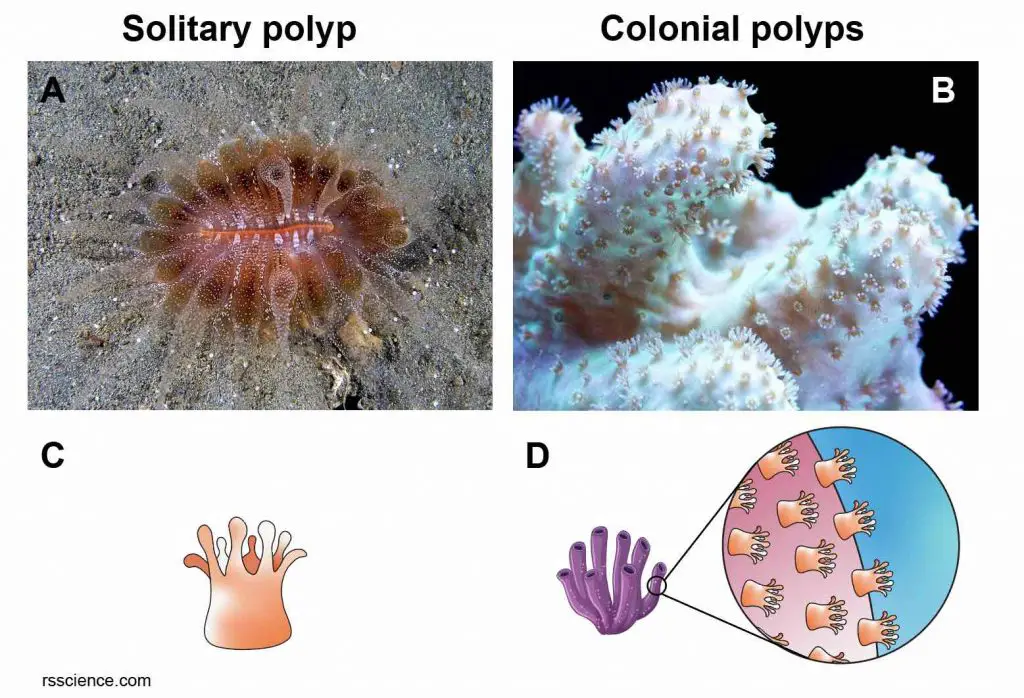

In scientific classification, corals belong to the phylum Cnidaria (nid-AIR-ee-a), which includes jellyfish, sea anemones, and hydra. They all have a common feature, using stinging cells on their tentacles to protect themselves or hunt for food. Cnidaria are predominantly marine species, but a smaller number of species (including hydras) are found in rivers and freshwater lakes.

[In this image] The examples of Cnidarians.

Cnidarians are incredibly diverse. Examples of Cnidarians include jellyfishes, sea anemones, corals, and hydras.

Images credit: jellyfish, sea anemone from NOAA, hydra from Stefan Siebert/Juliano Lab.

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Cnidaria

Class: Anthozoa (corals and anemones)

Subclass – Hexacorallia (hard corals with 6-fold symmetry)

Order – Scleractinia (stony corals)

Subclass – Octocorallia (soft corals with 8-fold symmetry)

Order – Alcyonacea (soft corals)

The anatomy of coral

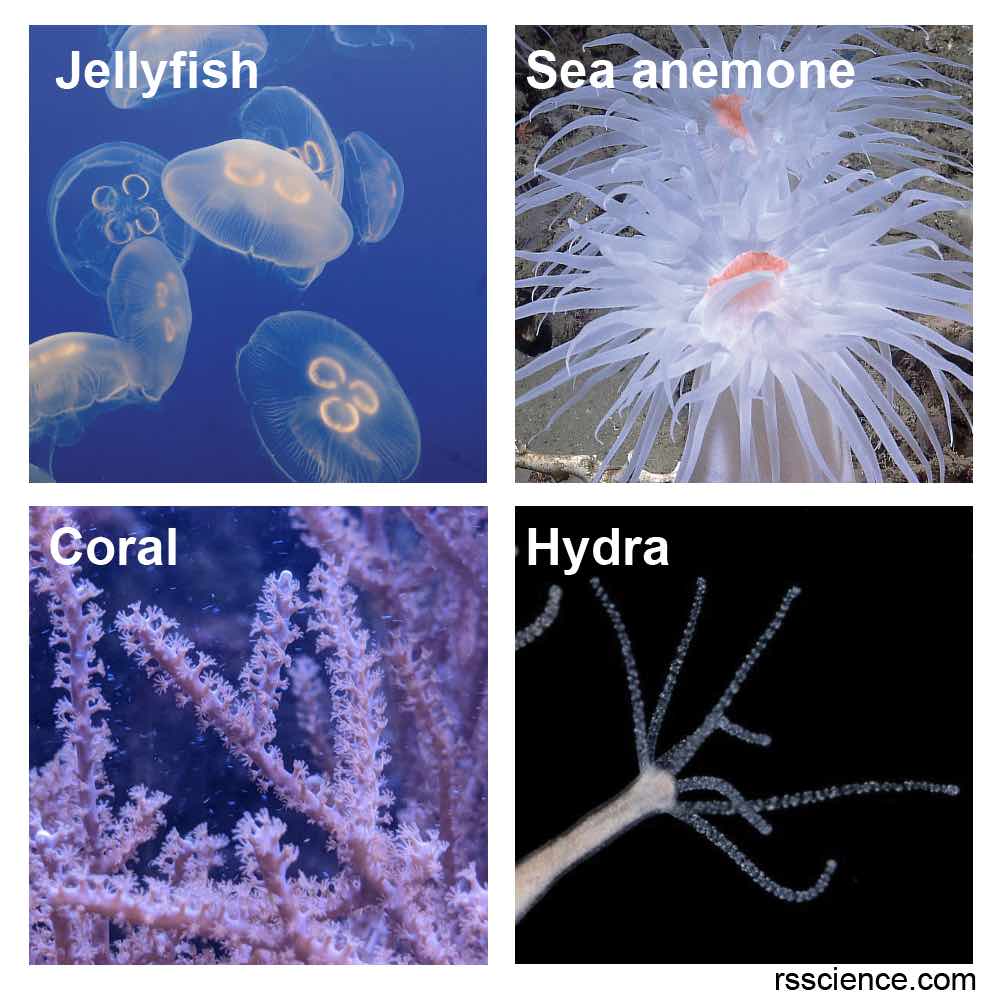

Coral polyps are soft-bodied with multiple arms or tentacles. Each tentacle is clothed with many stinging cells. Upon contact with prey, the contents of the stinging cells are explosively discharged, firing stings that can paralyze small animals.

Many corals form a symbiotic relationship with the zooxanthellae, a yellowish-brown dinoflagellate, which live in the cytoplasm of the polyp cells. Zooxanthellae can produce energy and nutrients via photosynthesis and supply energy to corals. In return, corals provide shelter places for zooxanthellae. The yellowish-brown zooxanthellae also give coral colors.

[In this image] Coral polyps anatomy.

Individual coral polyps exhibit one mouth in the center and multiple tentacles. Each tentacle is covered with highly specialized stinging cells. Stinging cells contain specialized structures called nematocysts, which look like miniature light bulbs with a coiled thread inside. Zooxanthellae are dinoflagellates, a group of protists that live within the tissue of the polyps.

Over time each coral polyp reproduces another polyp connected to it, which forms a structure, called a coral colony. Every coral colony has its own shape and size.

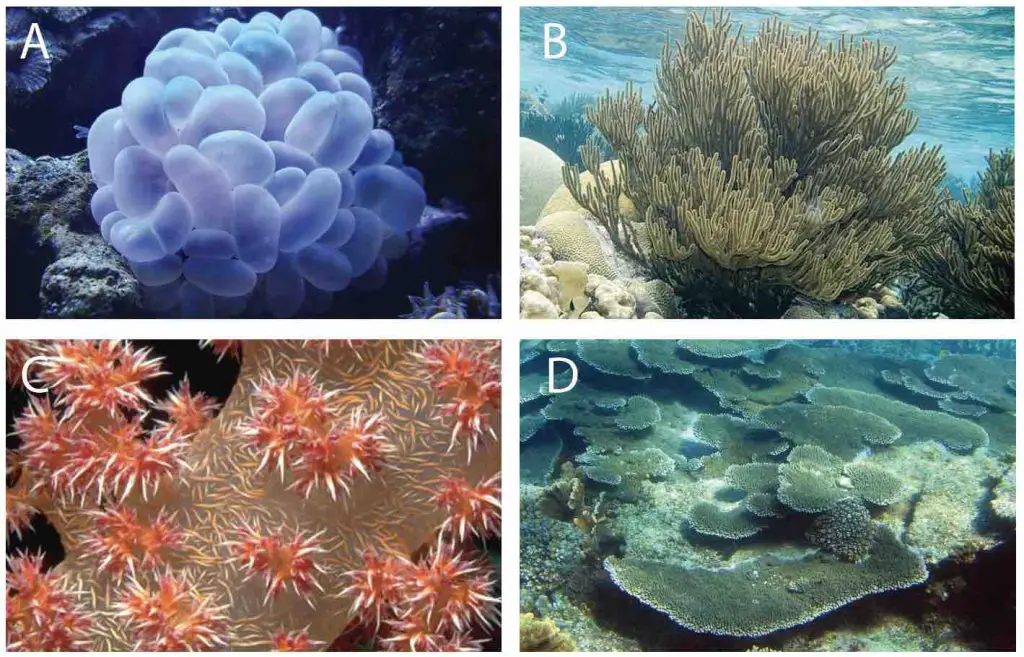

[In this image] Examples of coral colonies with different shapes.

(A)bubble coral, (B) sea rod coral, (C) orange soft coral, and (D) plate coral.

Image source: wiki, wiki, sea and sky, freeimages

Two types of corals

There are two main types of corals: hard corals and soft corals.

Hard Corals

Hard corals, also known as stony coral, produce a rock-like skeleton made of calcium carbonate (CaCO3). Hard corals are primary reef-building corals. As they grow, their skeleton builds up to form the foundation of a coral reef and this foundation also provides a structure for baby corals to sit on it.

Hard corals that form reefs are called hermatypic corals. Corals that do not contribute to coral reef development are referred to as ahermatypic corals.

A hard coral polyp is held in place by its hard cup base. Above the base is the soft body with stinging tentacles surrounding its edge. The polyp pulls its soft body and tentacles inside its hard cup base to protect itself. There are about 650 known kinds of hard coral polyps.

Hard coral tends to feed during the night. Hard corals have six tentacles or multiples of six (i.e. 6, 12, 18, 24…) while soft corals have eight tentacles or multiples of eight on each polyp.

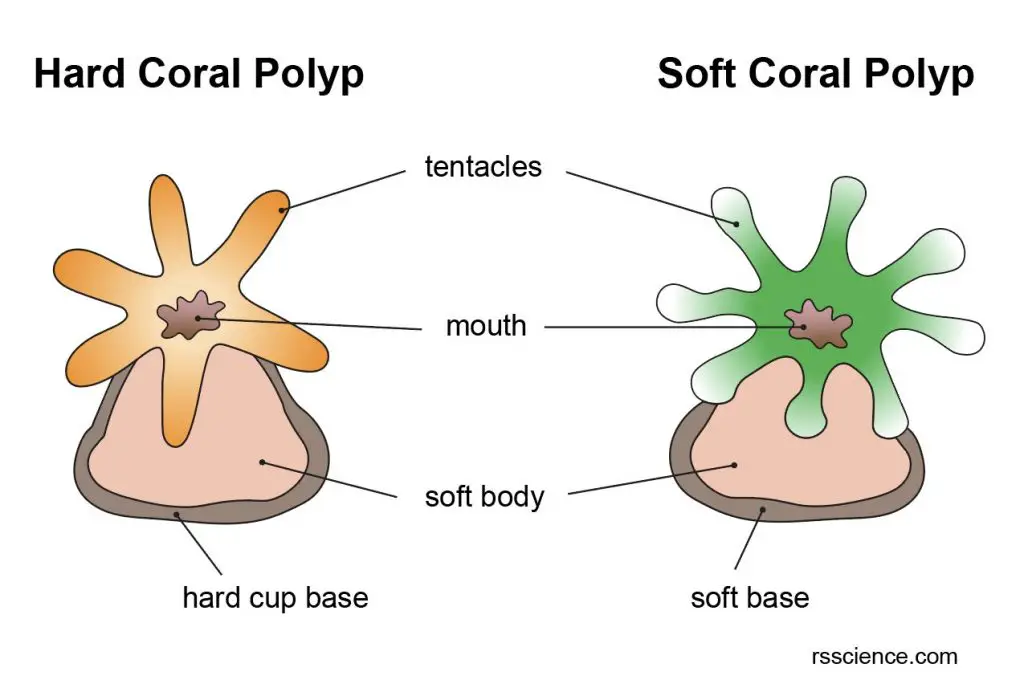

[In this image] Illustration of a hard vs. soft coral polyp.

Both hard coral polyps and soft coral polyps have soft bodies with a month and multiple tentacles. Hard coral polyp holds itself in place by its hard cup base, while soft coral polyp uses its soft base. Hard corals have 6 tentacles while soft corals have 8 tentacles.

Examples of hard coral are staghorn coral, table coral, brain coral, elkhorn coral, great star coral, leafy coral, branching coral, and honeycomb coral.

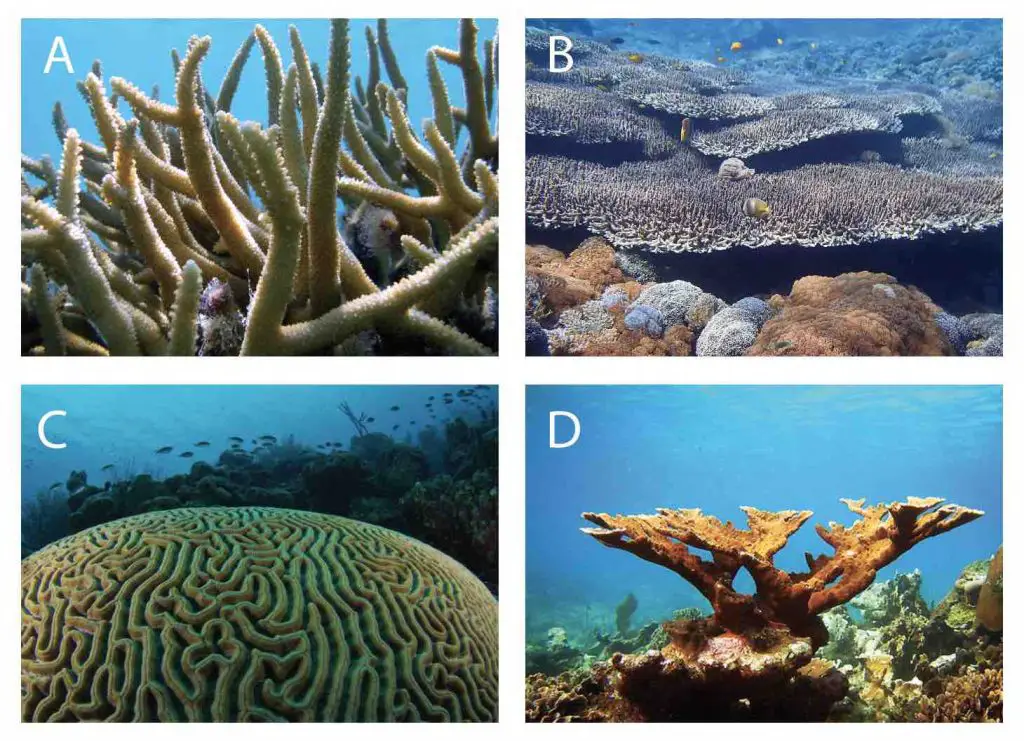

[In this image] Examples of hard corals.

(A) Staghorn coral, (B) Table coral, (C) Brain coral, (D) Elkhorn coral.

Image source: (A) ARC centre of Excellence on Flickr, (B) Janne Moren on Flickr, (C) Darren on Flickr, (D) diver_meg on Flickr.

Soft Corals

Soft corals are soft and bendable. They do not have stony skeletons and do not form reefs. Due to lacking stony skeletons, they sway back and forth with the motion of the current, appearing to be more like plants. Like hard corals, they also like to form colonies. Visually, soft coral colonies look like trees, bushes, fans, and grasses.

Unlike the hard corals that secrete calcium carbonate, soft corals secrete calcium or aragonite (minerals) sclerites. Sclerites are microscopic sharp-pointed structures that help to attach themselves to substrates and support the structure of the corals.

Soft corals build beautiful structures by reproducing themselves. There are about 1800 known kinds of soft coral polyps.

The color of soft corals tends to be brighter, and therefore, attracts many animals, such as fish, shrimps, and sea slugs to make their home in the colonies of soft corals. Often, these animals are camouflaged by having an identical color pattern to the soft coral that they live on.

Examples of soft corals are sea fan coral (Gorgonian), sea pen coral, sea whip coral, spiral coral, tree coral, and bushy soft coral.

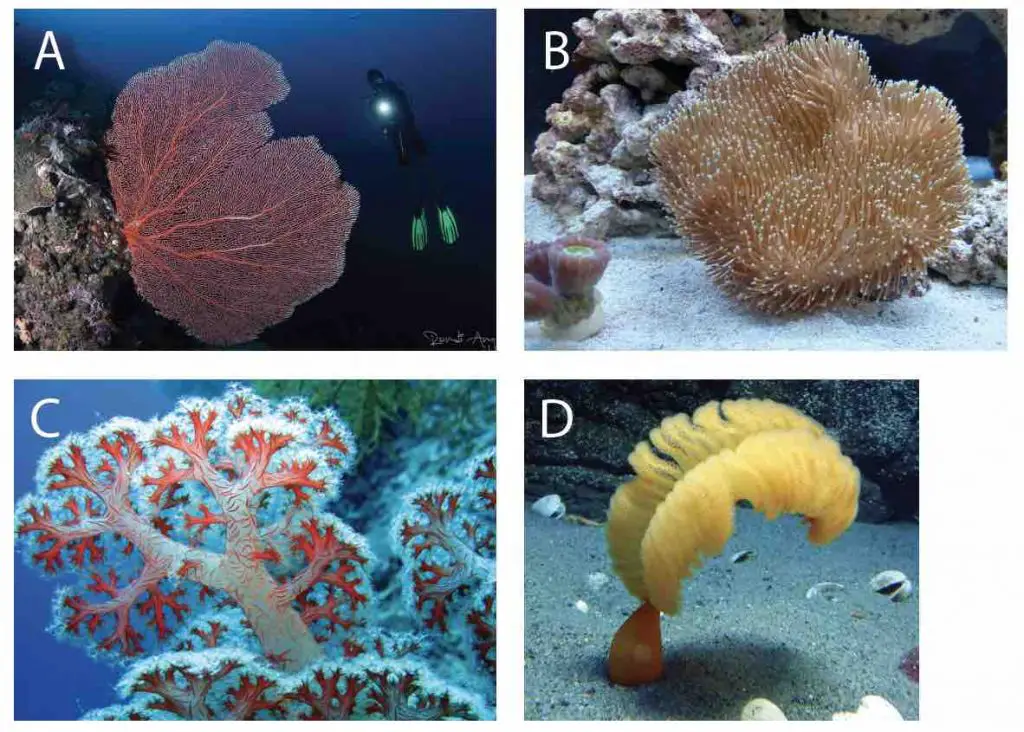

[In this image] Examples of soft corals.

(A) Sea fans, (B) Toadstool Coral, (C) Tree Corals, (D) Sea Pens.

Image source: (A) Randi Ang on Flickr, (B) Alexandria Smith on Flickr, (C) sarah faulwetter on Flickr, (D) Vic high marine.

Coral Reef Zones

Different organisms, including corals, live in specific parts of the reefs. Scientists divide coral reefs into zones, based on the location of these reefs and characteristics, such as depth, light intensity, wave energy, temperature, and water chemistry.

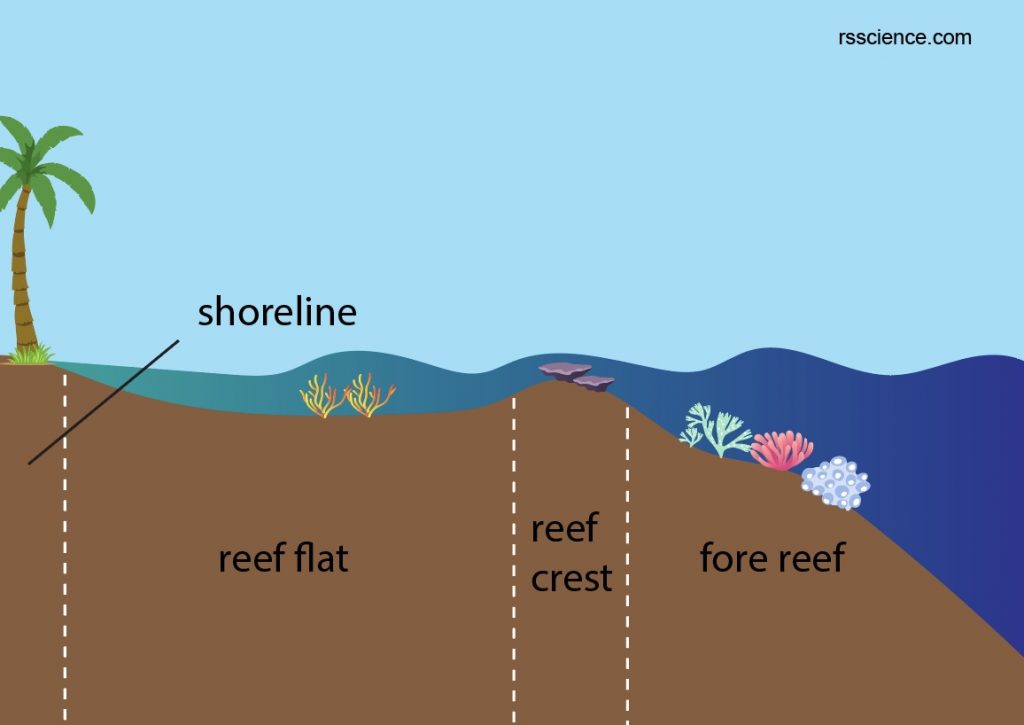

The most common type of reef is called the fringing reef, which grows outward from the coastlines of islands and continents. The fringing reef can be divided into three zones: reef flat, reef crest, and fore reef.

[In this image] Illustration of fringing reef.

Image credit: Thinga

Reef flat zone

The reef flat zone is close to the shoreline, where the water is shallow. This area is often protected from wave action. It can extend for feet to miles, and its depth can range from inches to several feet. The temperature in this area can be very high (over 104oF/ 40oC), and coral can be exposed to air during the low tide. Therefore, coral in this zone has to tolerate these extreme environmental conditions. Seagrasses, seaweeds, and soft corals (sea rod coral) are often found in this zone.

[In this image] Illustration of zonation on the coral reef.

Three main zones: (1) reef flat, the sheltered area between the reef and shore; (2) reef crest, the exposed top of the reef; (3) fore reef, the area immediately below the reef crest facing the ocean.

Reef crest zone

The reef crest is the highest point of a coral reef, located between the reef flat and the fore reef. This area is often exposed during the low tide and receives the strongest impact of wave energy. This zone also received the greatest amount of sunlight because it is closest to the water surface. Corals that survive in this zone must have strong and short structures that can withstand heavy wave action, high light intensity, and air exposure. Examples are elkhorn coral and star coral.

This zone can be dominated by calcareous coralline red algae in the Pacific and Indian oceans, therefore, this zone is often referred to as the algal ridge.

[In this image] Coralline algae.

Image credit: NOAA’s National Ocean Service

Fore reef zone

The fore reef zone is farthest away from the shoreline, where the water is deeper than in the other zones. It slopes downward and can reach great depth. Many corals thrive in this area, particularly between 15-65 feet (5-20 meters) deep, which receives relatively low wave action and light intensity. This area has the greatest diversity of corals, such as bolder coral, lettuce coral, sea fan coral, plate coral, leafy coral, and fire coral.

How do corals reproduce?

Corals reproduce asexually and sexually.

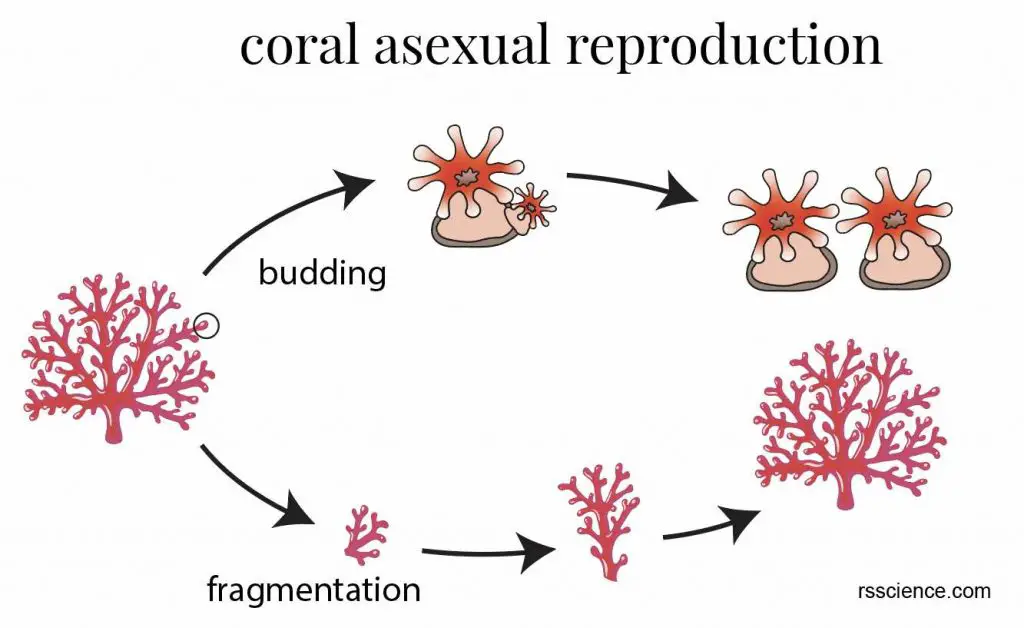

Asexual reproduction

Asexual reproduction only requires one parent. The daughter organism has an identical genome to its parent (ie., clone). Corals reproduce asexually mainly by fragmentation and budding.

[In this image] Corals reproduce asexually mainly by budding and fragmentation.

Budding

All the colonial coral can use budding for asexual reproduction. A small bulb-like projection (bud) grows out from a parent polyp and this bud gradually grows bigger and bigger. Then, the bud breaks off from its parent to form an independent polyp.

Fragmentation

A piece of coral is broken off from the parent coral due to a storm or human disturbance, it can grow and develop into a mature coral colony. This method is often used by people to restore coral reefs.

Sexual reproduction

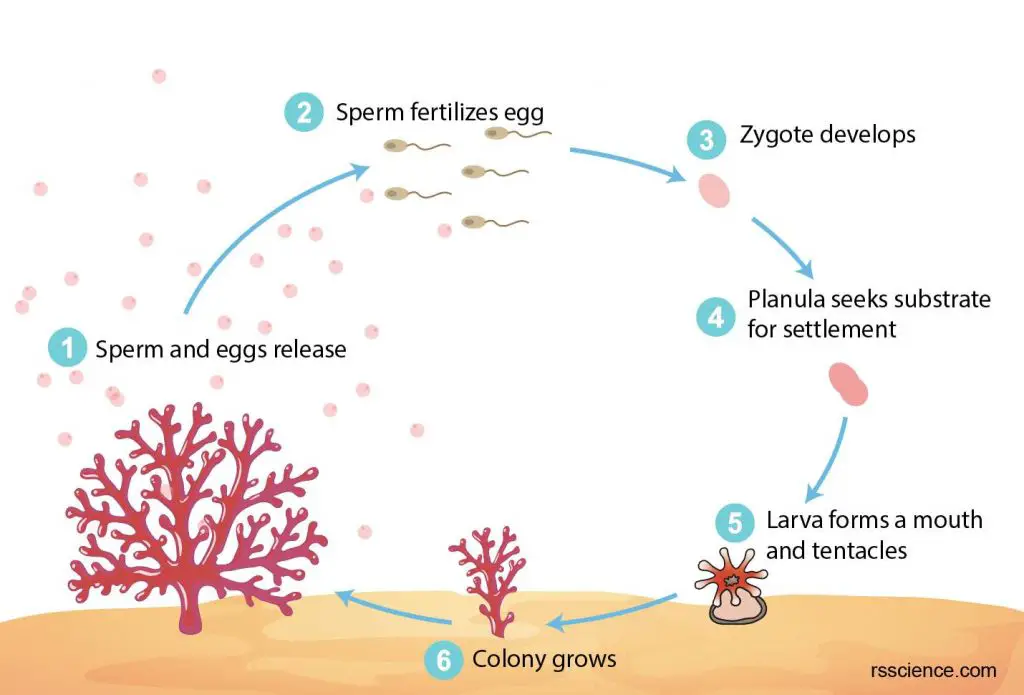

Sexual reproduction starts with sperm and egg production. The majority of coral species are hermaphroditic, meaning that they produce both sperm and eggs in individuals. The rest of the corals have separate sex; ie., either male to produce sperms or female to produce eggs. Fertilization occurs when a sperm and egg combine to form a new organism.

The majority of corals release their sperms and eggs into seawater at the same time, referred to as synchronous spawners. The fertilization occurs in the seawater, outside the body of the coral polyp (external fertilization).

Other corals fertilized their egg internally in the gastrovascular cavity, and allow them to grow into tiny oval larvae, called planulae (plural, the singular is planula). The planula drifts with the current until they find a suitable place to settle down. It will grow to a new polyp and then develop into a coral colony.

[In this image] The sexual reproduction and life cycle of coral.

(1) The mature corals synchronize their spawning to release gametes bundles, which contain sperm and eggs. (2) Sperm fertilize eggs. (3) Fertilized eggs undergo cell divisions. (4) Planulae larvae drift with current for days to weeks and actively seek suitable substrate to settle down. (5) Larvae form mouths and tentacles. (6) Polyps grow their colonies through polyp budding.

The spawning event happens at a certain time of the year, usually several days after a full moon. The factors that affect the spawning include the lunar cycle, sea temperature, tidal cycle, current, salinity, chemical signaling, storms and weather conditions, etc.

[In this image] Coral releases bundles of eggs and sperm.

Photo credit: Mikaela Nordborg/ Australian institute of marine science

Q&A

Is coral an animal, plant or rock?

Corals are marine animals that resemble miniature sea anemones. Corals are neither plants nor rocks.

Reference

Coral Reefs by Gail Gibbons

Coral identification

NOAA coral reef conservation program

https://www.livingoceansfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/U11-Reef-Zonation-Background.pdf