This article covers

Introduction

Birds have the ability to fly, something that humans have always been fascinated by. We often use flight as a metaphor for freedom, and it’s no wonder that many of us have dreamed of being able to fly like birds.

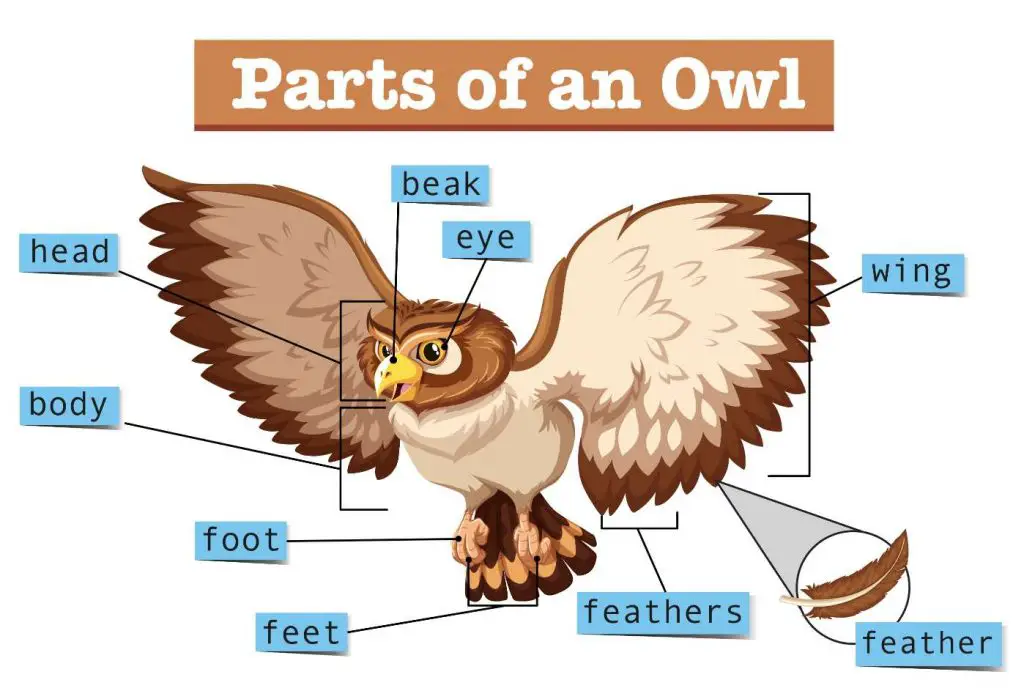

[In this image] The anatomy of an owl – you can see the bird is covered by feathers.

Image source: Freepik

[In this image] It’s every kid’s dream to fly like a bird.

Image source: Freepik

Why can’t humans fly, but birds can? Simply put, it’s because God has given them wings. These wings are covered with lightweight but strong feathers, which allow birds to fly, something that even our scientists are still working to understand.

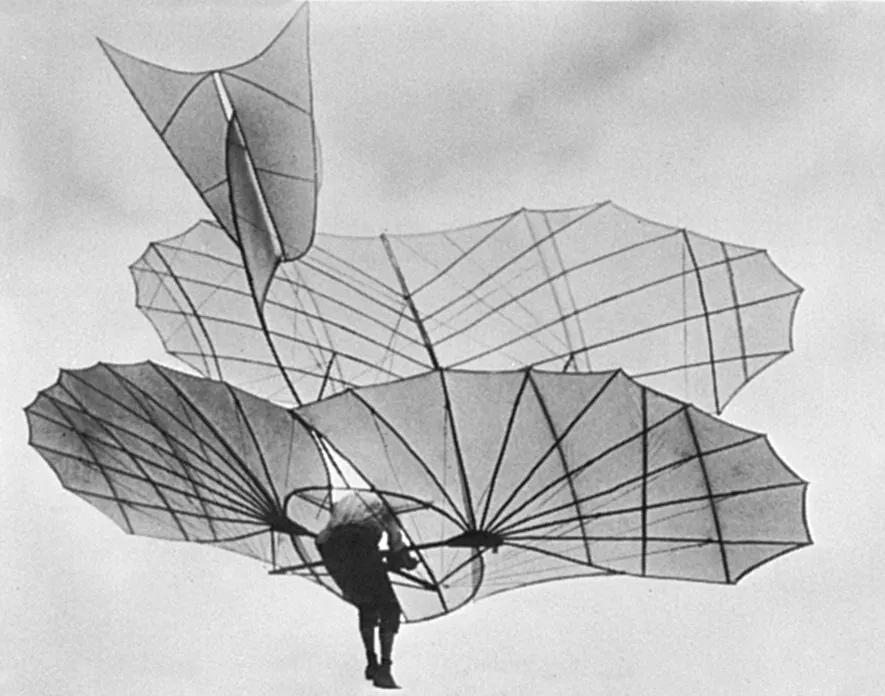

[In this image] In 1895, German aviation pioneer Otto Lilienthal piloted one of his flying machines by learning what a bird looks like. Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. (digital id. ppmsca 02545)

In this article, we will examine one of the most well-known features of birds: feathers! We will start by exploring the different types and functions of feathers. Next, we will use a microscope to get a closer look at how feathers work. Finally, we will discuss the relationship between birds and dinosaurs, including the possibility that T. Rex may have been a flurry giant chicken!

[In this image] Feathers are an essential and remarkable feature of birds.

They serve a variety of important functions and come in an incredible range of shapes, sizes, and colors. Whether you’re an avid birdwatcher or simply appreciate the beauty of nature, there’s no denying the magic of feathers.

Image source: Bay Nature

What You Need To Know About Feathers

What are feathers?

Feathers are the magic material that covers the bodies of all birds. Some feathers are tiny and downy, while others are large and brilliantly colored. Feathers are not only for flying; they are also great for insulation, which is why even flightless birds like ostriches and penguins have them.

[In this image] A collection of different feathers.

Image source: flickr

Who has feathers?

Feathers are unique to birds. While other animals, such as bats, lizards, and squirrels, may exhibit some characteristics similar to birds, such as the ability to fly, lay eggs, or build nests, none of these animals have feathers. Feathers are the main characteristic that distinguishes birds from all other animals.

[In this image] A T-rex and a Parrot. Paleontologists have found enough fossil evidence to support the theory that dinosaurs are likely the ancestors of birds.

Do feathers regrow?

Feathers have to handle a lot of wear and tear, so each year, birds grow a new set to replace the old ones. This is called molting. Some birds will molt once a year; others do it twice.

What do feathers do? – Feather Function

Feathers are amazing biological structures that are found in many different sizes, shapes, colors, and patterns. They are truly impressive. Some species have feathers that are nearly transparent, while others have feathers that are so brightly colored that they seem to glow. Many people are familiar with the long, sleek feathers of birds like swans and cranes, but some species have feathers that are fluffy and downy, while others have feathers that are bristly and stiff. Feathers evolved into these different types for a central reason – to help the “birds” survive better!

[In this image] Functions of bird’s feathers.

One of the primary functions of feathers is for flight. The shape and structure of feathers, especially on a bird’s wings, allow them to lift off the ground and fly through the air. However, feathers have other functions as well. They help birds regulate their body temperature by trapping heat and dissipating excess heat. They also serve as camouflage, helping birds blend in with their surroundings. In some species, feathers are used in courtship displays and territorial displays to attract mates or defend territory.

Below we summarize how feathers can do in the bird’s activities.

Flight

Feathers allow birds to fly. The long wing feathers occupy most part of the bird’s wings. These feathers are strong enough to withstand the demands of flight. Tail feathers are also classified as flight feathers and are essential for steering.

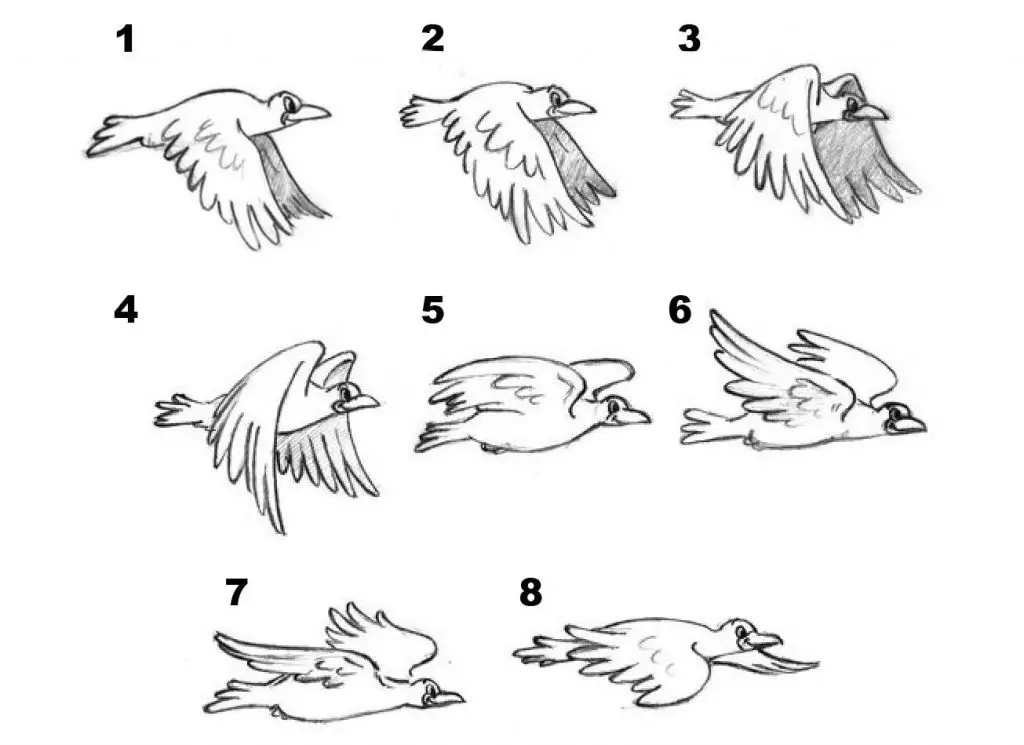

[In this image] The steps of a bird flying.

The main function of feathers for flight is to provide a surface for air to flow over. When a bird flaps its wings, it generates an upward force called lift, which counteracts the force of gravity and allows the bird to take off and fly. The shape and arrangement of feathers on a bird’s wings are designed to create this lift.

[In this image] Birds use their wings to generate lift, with which they overcome gravity.

The leading edge of a bird’s wing is usually more curved than the trailing edge, which helps to generate lift. The feathers on the leading edge of a bird’s wing are also more rigid than those on the trailing edge, which helps to maintain the shape of the wing and keep it stable during flight.

In addition to providing lift, feathers also help birds to control their flight. The feathers on a bird’s wings can be adjusted to alter the shape of the wing and change the direction of flight. For example, a bird can change the angle of its feathers to turn or bank, or it can alter the shape of its wings to change its speed or altitude.

Insulation

A bird’s feathers play an important role in keeping its body temperature, much as hair does for mammals. They are excellent insulating materials and help birds to retain heat and stay warm in cold weather.

[In this image] Down feather is very soft and fluffy, making it an excellent insulating material. Down jackets are warm because there are downy feathers packed inside as insulation materials.

Image source: wiki

Birds are endothermic (warm-blooded), meaning they are able to maintain a constant body temperature of around 40°C. Birds have small, soft feathers called down, which lie against the skin and help to keep the bird warm. Down is highly effective at insulating and retaining heat, and is often used in the production of quilts and duvets. In cold weather, a bird will also fluff out its body feathers to create a layer of trapped warm air around its body.

[In this image] A group of Canada Geese paddling along on a cold winter day. Can you guess how many feathers cover this goose? Hundreds? Thousands? – The answer is that one Canada Goose has between 20,000 and 25,000 feathers!

Image source: Audubon

[In this image] The essential items for every Mt. Everest mountaineer include down-filled jackets, suits, mitts, and sleeping bags. Down is a fantastic insulator as the loft (or fluffiness) of down creates thousands of tiny air pockets which trap warm air and retain heat, thus helping to keep the wearer very warm in cold winter weather.

Image source: Redbull

Waterproofing

Feathers arranged in an overlapping pattern on a bird’s body, function like a waterproof coat, allowing rain droplets to roll off the bird’s back. Birds constantly groom and preen their feathers to maintain them in good shape. For ducks and seabirds that spend most of their time in the water, maintaining a waterproof coat is critical for survival. However, if the feathers of a seabird become coated in oil, it can disrupt the waterproofing, leaving the bird waterlogged and helpless.

[In this image] A red-necked grebe is preening its feathers.

Image source: International bird rescue

Display

Color feathers help the birds show off! A set of beautiful, eye-catching feathers on male birds can be very attractive to their potential female partners – we call this “courtship display.” Some feathers are so highly modified for display that they almost don’t look like feathers at all. These display feathers can be found on the wings, body, tail, or even head of the bird.

[In this image] The crown on a Wood Duck’s head (left) and the spiral tail of a King Bird-of-Paradise (right) are two examples of highly modified feathers for the male’s courtship display.

Image source: BirdAcademy

[In this image] The amazing diversity of colors and patterns exhibited by more than 10,000 bird species found in the world.

Image source: BirdAcademy

Intimidation

Not all showy feathers are used for courtship; some are used in displays of aggression. For example, Blue Jays lower their crests when they are at rest or with their family but raise them during aggressive interactions.

[In this image] A blue jay raises its crest in response to unfriendly encounters.

Image source: Birdwatchingbuzz

Camouflage

The colors and patterns of a bird’s feathers can serve as a form of camouflage for birds, helping them to blend in with their surroundings and avoid predators.

For example, a bird that lives in a forest may have feathers that are brown or green, which can help it blend in with the trees and foliage. A bird that lives in an open grassland may have feathers that are sandy or grass-colored, which can help it blend in with the ground.

Feathers can also be used to break up a bird’s outline, making it harder to spot. For example, a bird that lives in a snowy environment may have feathers with white edges, which can help to camouflage it against the snowy background.

[In this image] A snowy owl. Photo: Zdeněk Macháček

Image source: Gage Beasley

Structures of Bird Feathers

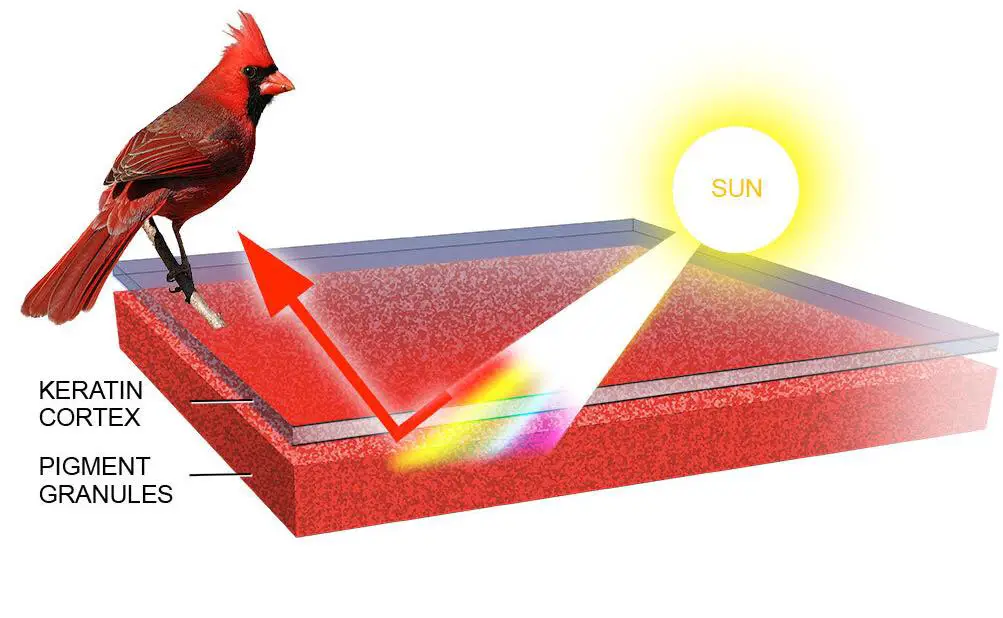

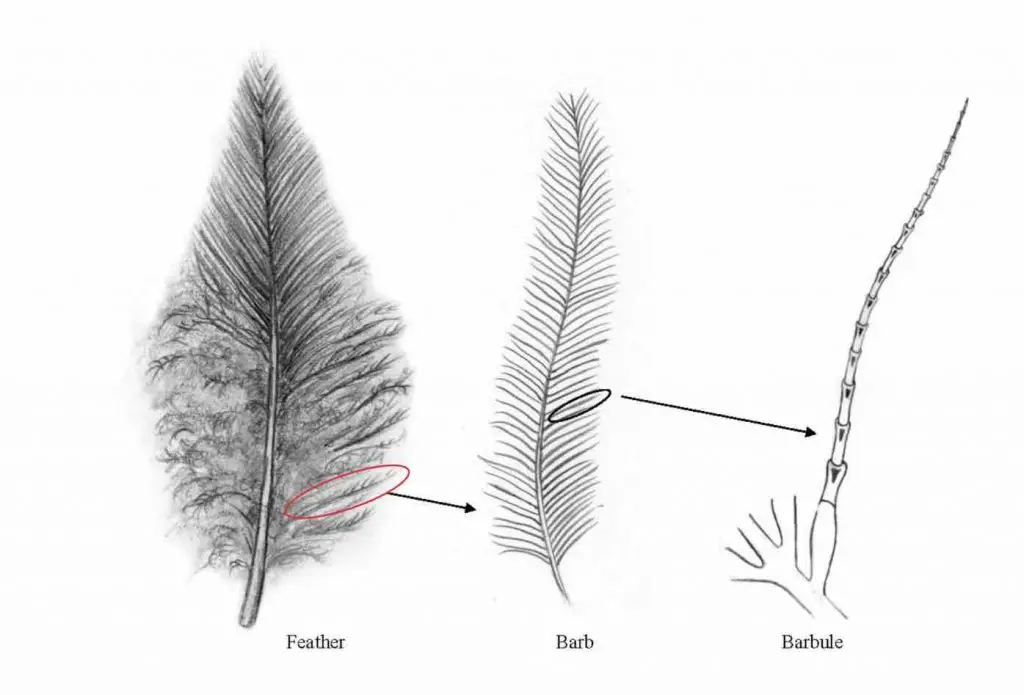

Although feathers come in an incredible diversity of forms, they are all made up of the same basic parts and arranged in a branching structure.

We can roughly divide the feathers into “wing feather” and “down” to study their structures. If you find some feathers, look at them under a microscope or magnifier to see if you can identify these structures.

Structures of wing feathers

Let’s look at the overall coverage of wing feathers on a bird’s wing.

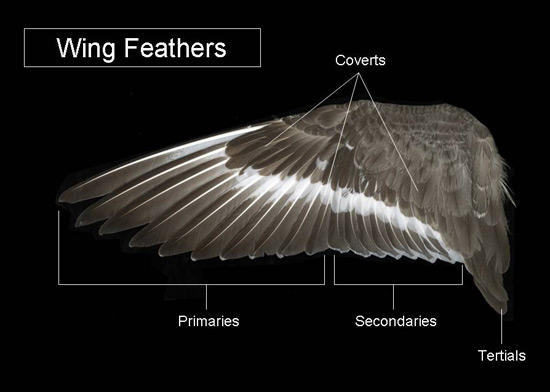

[In this image] The major types of wing feathers.

Image source: US Fish and Wildlife Service

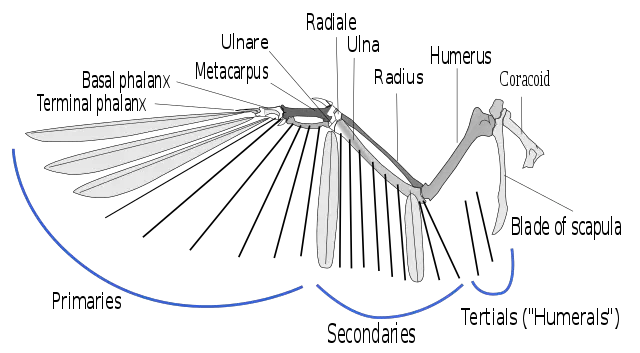

- Primary feather – one of the wing’s outer flight feathers, which are attached to the fused bones of the bird’s “hand.” Most bird species have 9-10 primaries.

- Secondary feather – one of the wing’s inner flight feathers, which are attached to the ulna bone in the bird’s “forearm.” The number of secondaries varies from 9-25 depending on the species.

- Tertial feather – the innermost flight feathers of the wing, attached to the humerus bone in the bird’s upper arm. There are usually 3-4 tertials.

- Remiges – the flight feathers of the wing, including the primaries, secondaries, and tertials.

- Coverts – the contour feathers that cover the bases of the flight feathers. Those on the upper (dorsal) surface of the body are called upper wing and upper tail coverts; those on the under (ventral) surface are called under wing and under tail coverts. In some birds, such as eagles, these are large enough to merit illustration in the Feather Atlas.

[In this image] Bird wing bone structure, indicating attachment points of remiges.

Image source: wiki

The closer view of a primary flight feather

The primary flight feather is the most complex feather. Let’s take it as an example and start our study from the roots of the feathers.

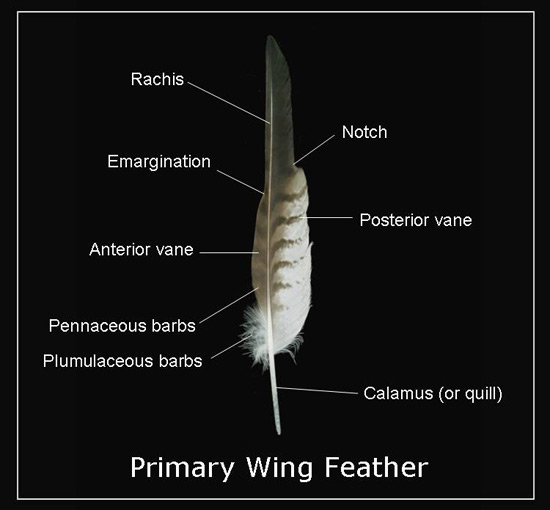

The basic terms that describe parts of a feather are illustrated below.

[In this image] You can see the calamus (or quill) extends into a central rachis which branches into barbs, and then into barbules with small hooks that interlock with nearby barbules.

Image source: US Fish and Wildlife Service

- Calamus or quill – the hollow portion of the feather shaft that attaches to the skin.

- Rachis – the calamus extends into a central rachis, which is the upper portion of the feather shaft and to which the barbs are attached.

- Barb – an individual strand of feather material, extending laterally from the rachis.

- Barbule – a lateral branch of a feather barb.

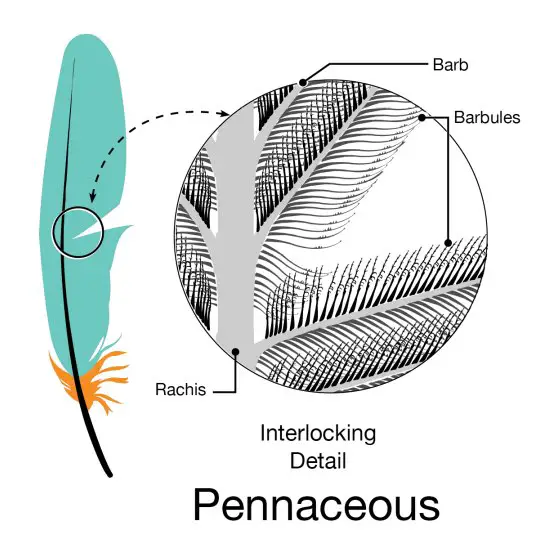

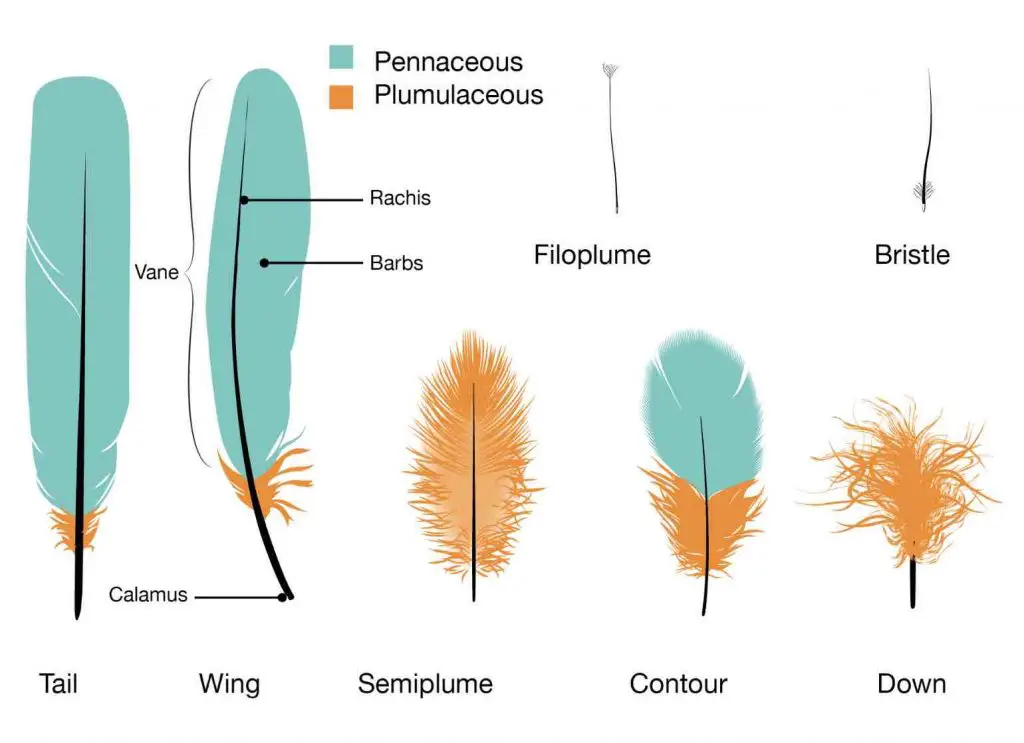

- Pennaceous Barbs – the portions of barbs with interlocking barbules that form a strong, but flexible wing plane (or called vane).

- Plumulaceous Barbs – the portions of barbs without interlocking barbules, forming a loose fluffy layer at the base of some feathers.

[In this image] A closer view of a wing feather.

The pennaceous portions are labeled in green color, while the plumulaceous parts are in orange color. You can see the hierarchical branching from the central rachis into barbs, and then into barbules.

Image source: wiki

You may notice that the central rachis divides the feather into two parts (called vanes). The Vane is the smooth feather surface formed by the interlocked pennaceous barbs. The anterior vane is on the forward side of the rachis (the leading edge). The posterior vane is the trailing edge of the feather.

Structures of downy feathers

The structure of downy feathers is much simple. Downy feathers look fluffy because they have a loosely arranged plumulaceous microstructure with flexible barbs and relatively long barbules. These hair-like structures can trap air close to the bird’s body and form an insulation layer to keep the bird warm.

[In this image] A closer view of a down feather.

You can see that a down feather is made of mainly plumulaceous parts.

Image source: BirdAcademy

What are feathers made of?

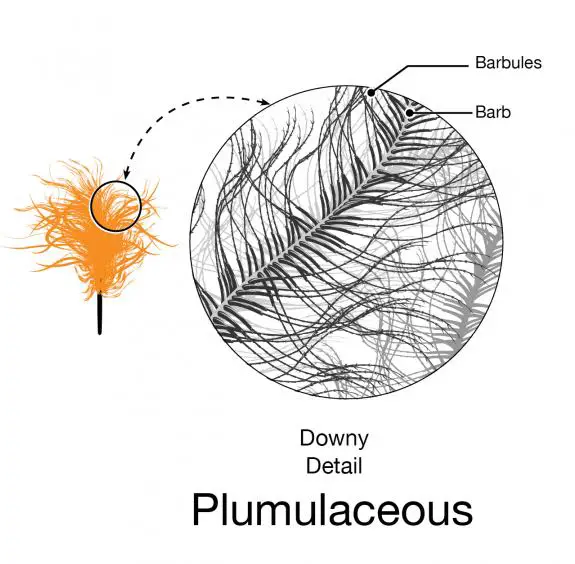

Feathers are composed of a lightweight material known as keratin, which is similar to the protein that makes up our nails and hairs, or the scales of reptiles. Muscles attached to the base of each one allow the bird to move it around. When examined under an electron microscope, scientists can observe how these keratin proteins form fibers and filaments that are organized into the rachis, barbs, and barbules.

[In this image] A molecular view of a bird’s feather.

Photographic images and micrographs depict the structure of a bird’s feather, which is composed primarily of keratin β-sheets.

Image source: Donato R.K. and Mija A., Polymers, 2020

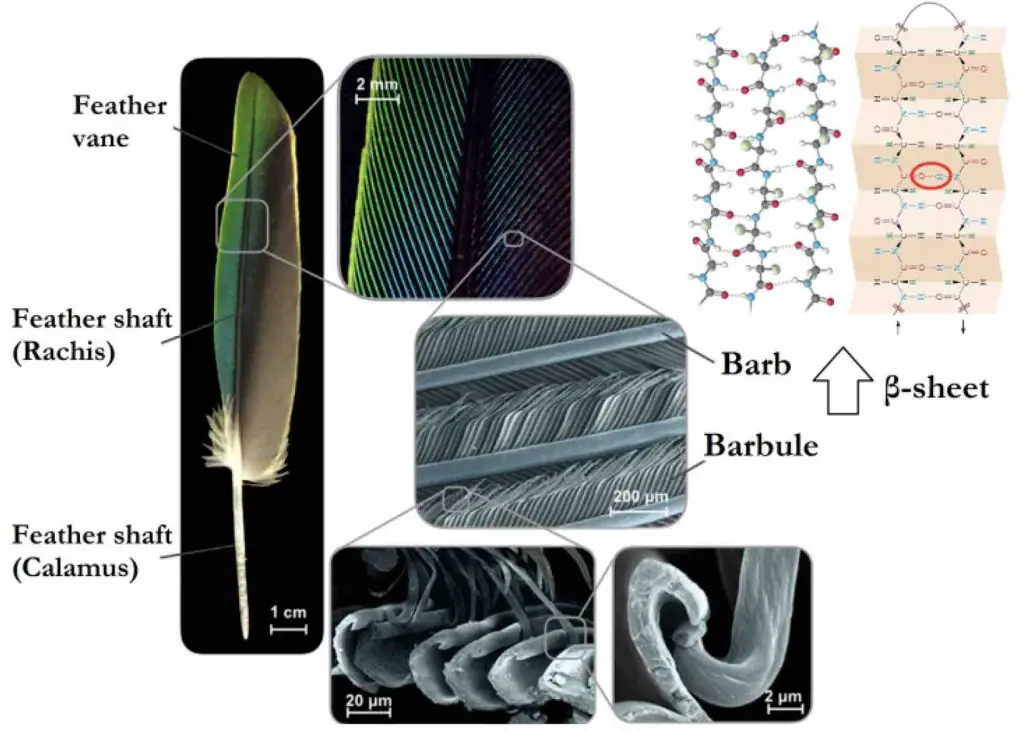

Why do bird feathers have different colors?

There are several ways that color is created in bird feathers. The pigments found in the keratin layers of feathers are the main contributors to feather color. Some of these pigments are produced by the bird’s body, while others are obtained from the bird’s diet, including plants, fruits, and insects.

[In this image] The bright red color of the cardinal comes from the pigment granules in its feathers. In this case, all but the red wavelengths are absorbed by the pigment granules.

Image source: BirdAcademy

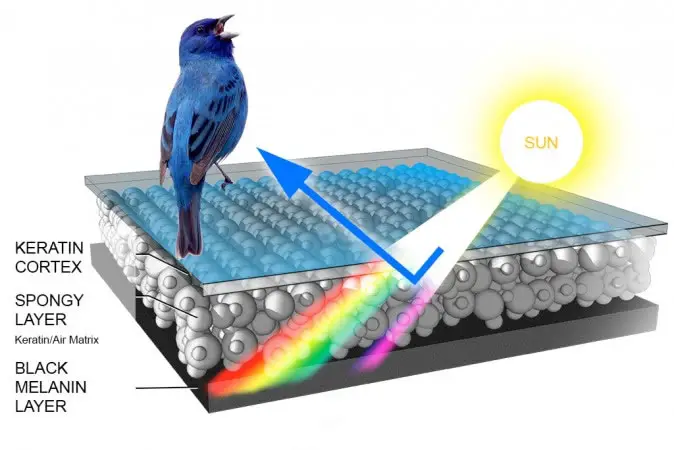

[In this image] Indigo Buntings’ blue color is produced by the refraction of light by an organized structure of keratin proteins in the feather. In this case, blue is refracted, and the remaining colors are absorbed by a layer of spongy materials.

Image source: BirdAcademy

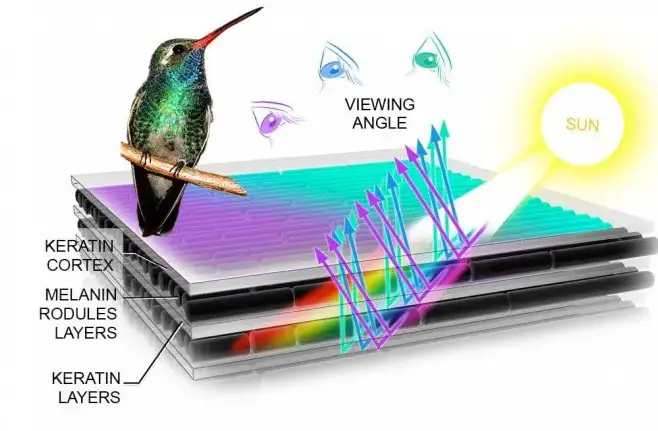

In addition to these pigments, the structure of a feather can also contribute to its color. For example, some feathers have a multi-layered structure that produces iridescent colors, such as the shimmering blue and green feathers of hummingbirds. The color of these feathers is created by the scattering of light as it passes through the different layers of the feather.

[In this image] Many hummingbird species have iridescent feathers which can change color with different viewing angles. These iridescent colors are the result of the refraction of incident light caused by the microscopic structure of the feather barbules.

Image source: BirdAcademy

Types of feathers

In this section, we will examine seven types of feathers that are located on different parts of a bird’s body.

[In this image] Feathers fall into one of seven broad categories based on their structure and location on the bird’s body.

Image source: BirdAcademy

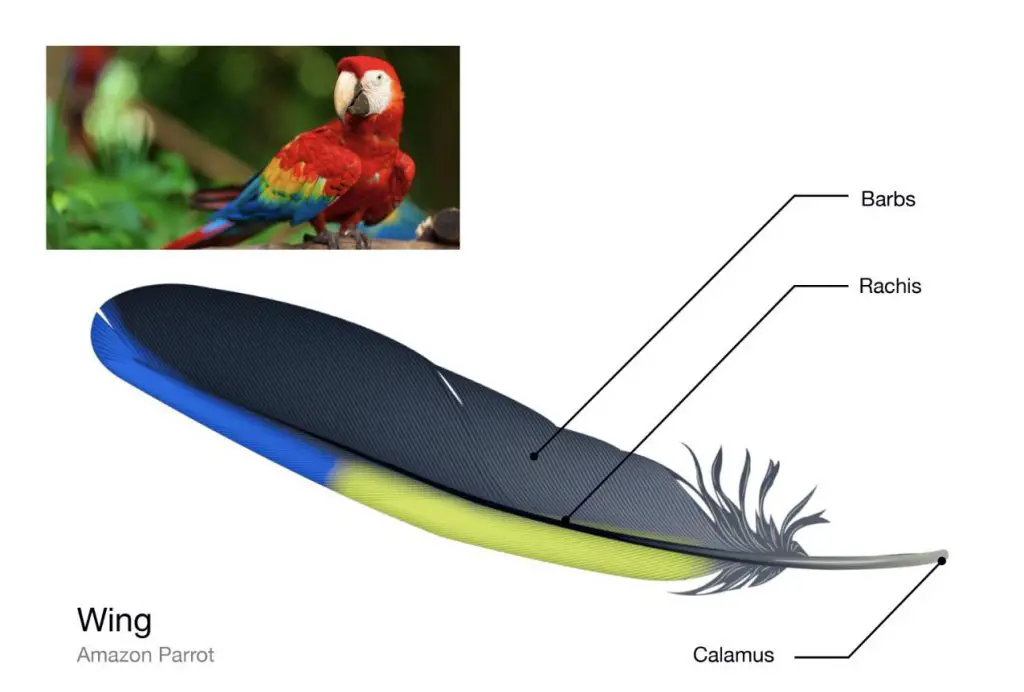

Wing feathers

Wing feathers are the feathers on a bird’s wings that are specialized for flight. They have a smooth surface that allows the air to flow over them easily. These feathers also have an interlocking microstructure that gives them a windproof surface.

Wing feathers are generally long and narrow, with an asymmetrical shape that has a shorter leading edge. They are made up of different types of feathers, including primaries, secondaries, and contour feathers.

The longest primary feather can be up to 38 cm in length.

[In this image] The wing feather of an Amazon Parrot.

Image source: BirdAcademy

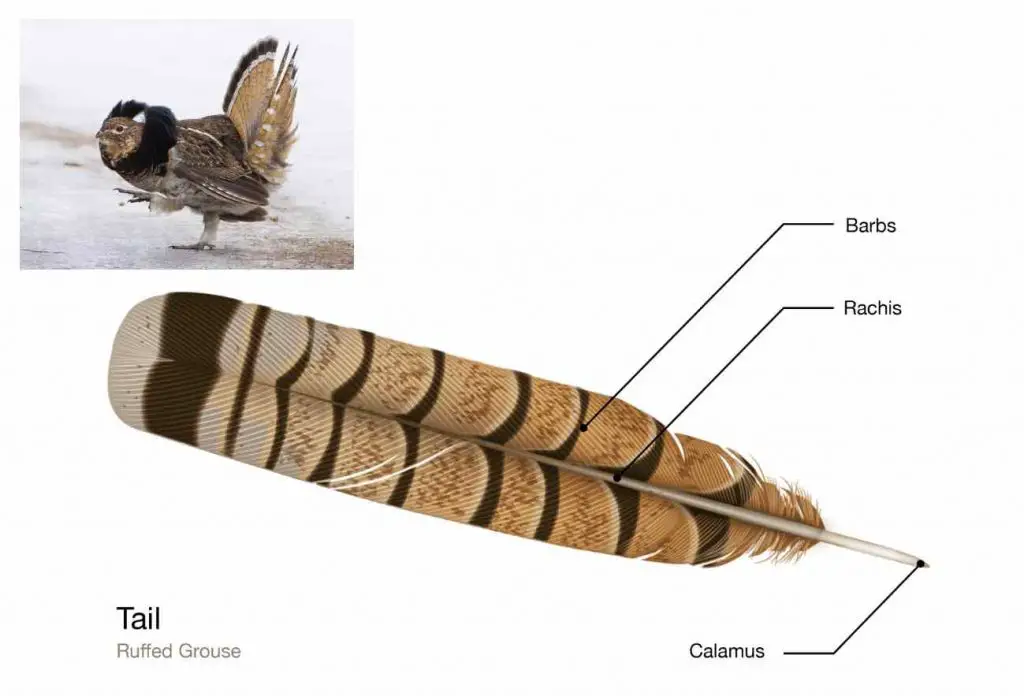

Tail feathers

Tail feathers, also known as rectrices, are the feathers located on a bird’s tail. These feathers are typically wider and more symmetrical than the flight feathers on the wings.

Tail feathers are used for various functions such as balance, steering, and signaling during flight. In some birds, the tail feathers are also used for display and can be spread out or fanned in a fan shape to attract a mate or intimidate a rival.

Some birds, such as peacocks, have evolved long, flowing tails with feathers that are primarily used for display and have little function in flight. The number and shape of the tail feathers can vary widely among different species of birds.

[In this image] The tail feather of a Ruffed Grouse.

Ruffed Grouse’s extravagant display includes long neck feathers to create a black “ruff” and fanning the tail to expose a dark band near the tip.

Image source: BirdAcademy

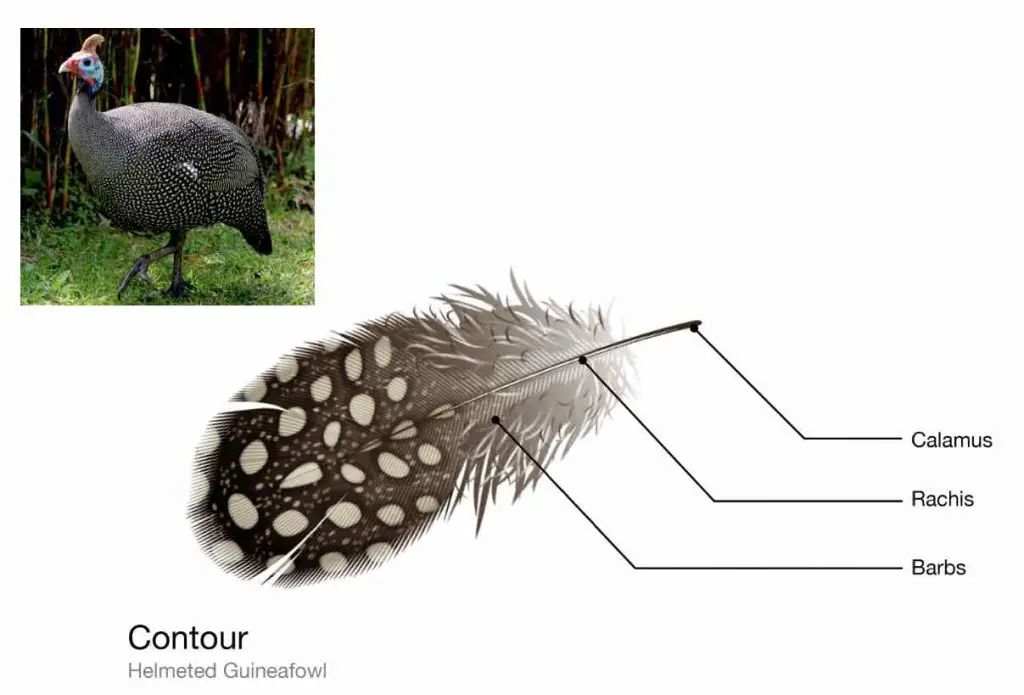

Contour feathers

Contour feathers are the feathers that cover a bird’s body and streamline its shape. They are also known as body feathers or covering feathers.

Contour feathers overlap one another to provide insulation and waterproofing for the bird. Colored contour feathers also help the bird display itself or blend into its surroundings.

The contour feathers on a bird’s wing are called coverts, which help to smooth out the shape of the wing. This creates an efficient airfoil that helps the bird fly by generating lift and drag, similar to an airplane wing.

[In this image] The contour feather of a Helmeted Guineafowl shows its spotted pattern.

Image source: BirdAcademy

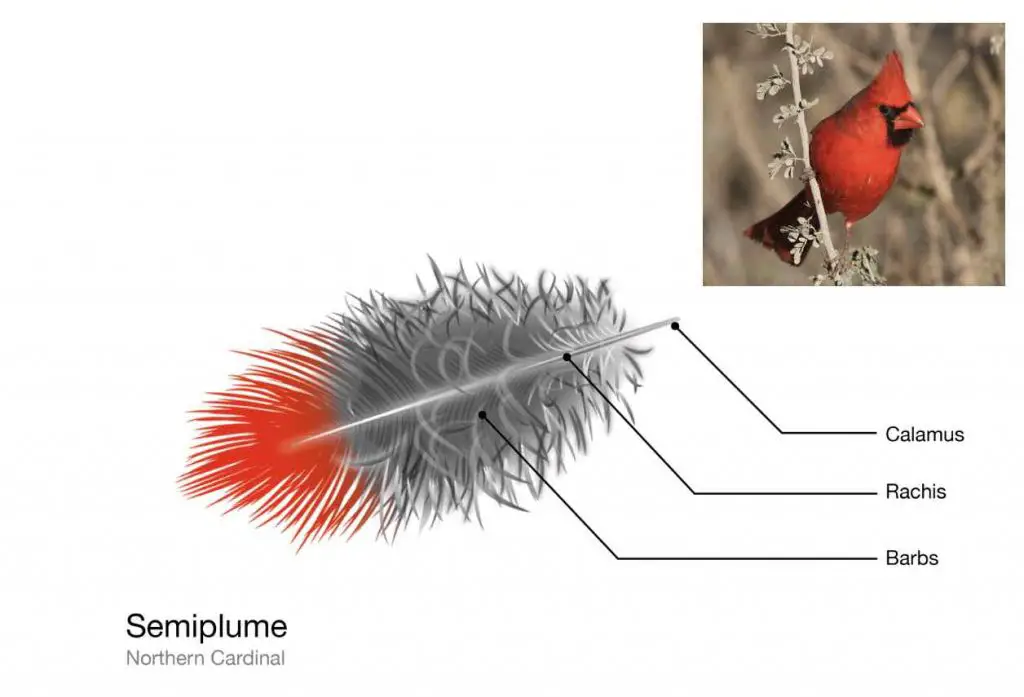

Semiplume feathers

Semiplume feathers are mostly hidden under other feathers and help to give a bird’s body shape and make it more aerodynamic in flight. They also provide padding, creating a fluffy insulating layer.

[In this image] The semiplume feather of a Northern Cardinal with a red color near its tip.

Image source: BirdAcademy

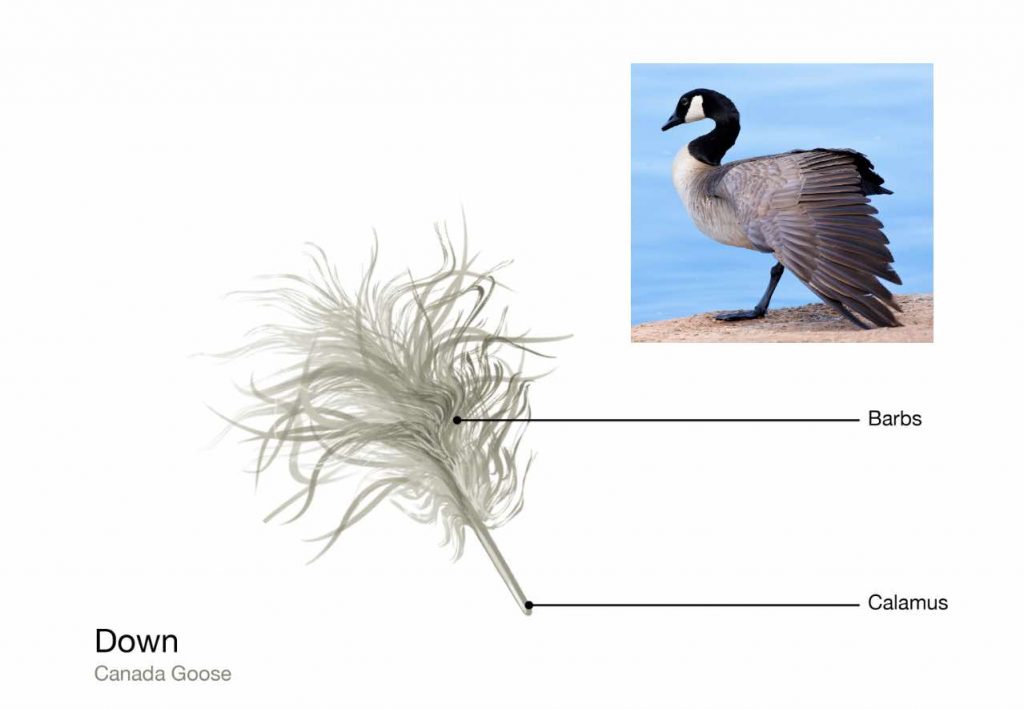

Down

Down feathers are short and fluffy, with a loose branching structure and little or no central rachis. They are the feathers closest to a bird’s body and help to trap body heat, ensuring that the bird stays warm and well-insulated on cold nights.

Down feathers from geese and ducks are used in jackets and bedding to keep people warm.

[In this image] The down feather of a Canada Goose can keep the bird’s body temperature in the winter.

Image source: BirdAcademy

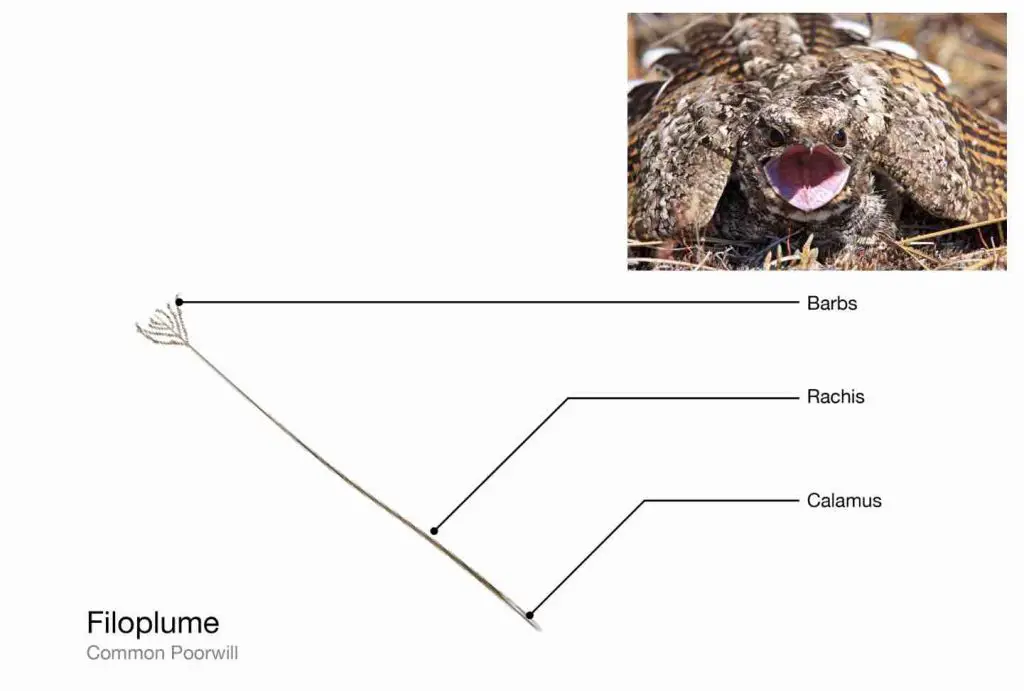

Filoplume

Filoplume feathers are short and thin, almost hair-like feathers mixed in among contour feathers. They function like the whiskers of mammals, helping to sense the position of the contour feathers and possibly adjusting them in response to air pressure.

[In this image] The filoplume feather of a Common Poorwill.

Image source: BirdAcademy

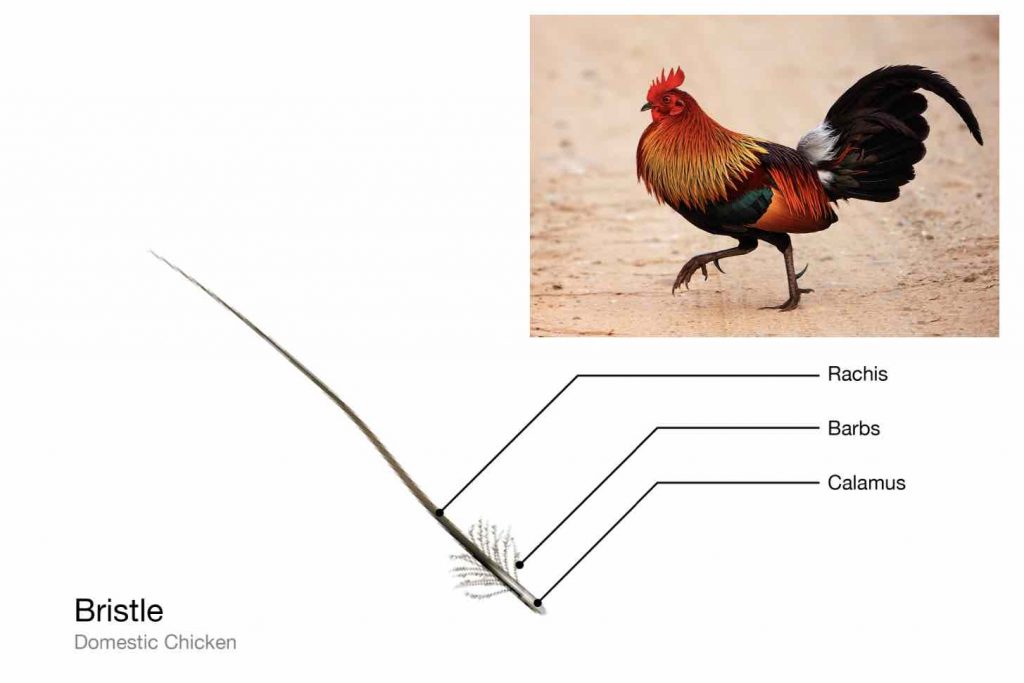

Bristle

Bristles are even simpler than filoplumes, and are generally found on a bird’s head. They have both a sensory and protective function, protecting the bird’s eyes and face.

[In this image] The bristle of a Domestic Chicken with a red color near its tip.

Image source: BirdAcademy

Look at Feathers under the microscope

It is important to use caution when handling the feather and the microscope to avoid damaging either one. You may also want to wear gloves to protect the feather from oils on your skin, as this can damage the feather.

Tools and materials

- Microscope: Stereo microscopes or USB microscopes are ideal for viewing the colors, patterns, and surface textures of feathers.

If you want to see the detailed microstructures, you may need a compound microscope. - Magnifier: If you don’t have a microscope, try a magnifier.

- Scissors, tweezers, and needles

They can help to handle the tiny feathers. - Blank microscope slides, coverslips, mounting media, and tapes

For compound microscope, you will need to prepare a mounted slide. - A notebook to draw the unique features and write down what you found.

Where to find feathers

- Birdshop/farm: Ask the owners if you can take one feather out in the name of science.

- Pick up feathers from your backyard or local parks. Make sure you wash your hands after handling everything!

- Find the fluffy down used to stuff soft cushions and bedding.

- Etsy

- Don’t touch or take feathers from dead animals – They could have diseases, like bird flu; If you spot unusual death of birds, you should report it to your local healthcare or wildlife departments.

How to look – steps

For a stereo microscope, USB microscope, or magnifier, you observe the feathers directly with a proper light source.

To look at bird feathers under a compound microscope, you will need to follow these steps:

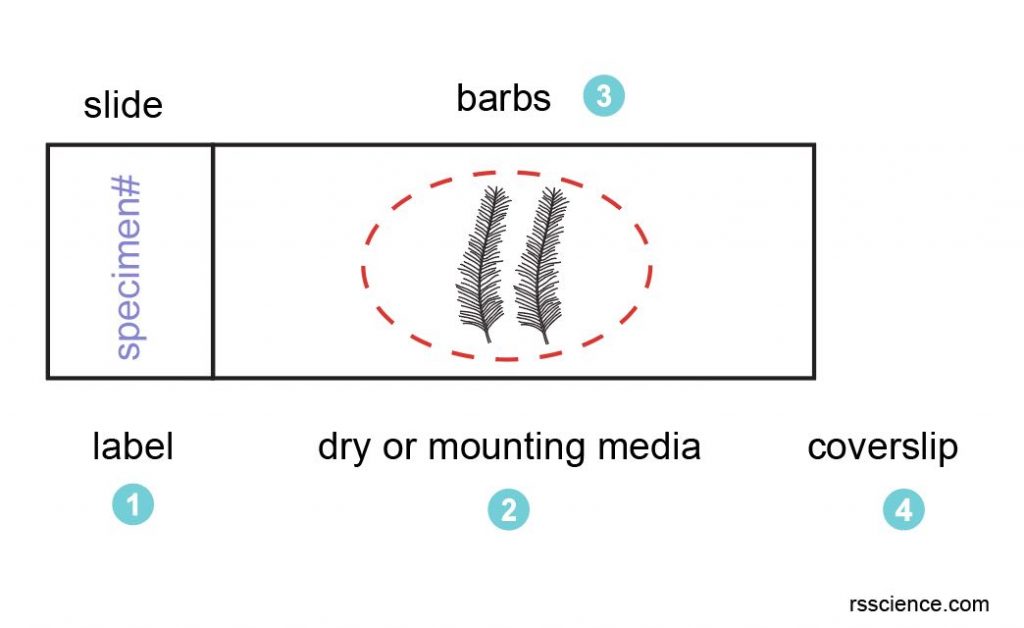

Step 1: Use scissors and tweezers to dissect a small piece of feather. Usually, we like to dissect pieces of feather barb. It is important to handle the feather gently to avoid damaging it.

[In this image] Illustration of the position of the barb and barbule to the feather (illustrated by Lisa Bailey).

Image source: Dove and Koch: Forensic Feather Identification

Step 2: Prepare a microscope slide by placing several small pieces of barbs. You can observe them in a dry condition by sticking the feather to the tape. Or you can add a drop of mounting medium (i.e., water or Xylene) and then cover the specimen with a coverslip. Using a liquid base can allow downy barbules to spread or float onto the microscope slide.

[In this image] Steps for microscope slide preparation of feather barbs.

Image source: modified from Dove and Koch: Forensic Feather Identification

Step 3: Place the slide on the microscope stage and adjust the focus so that the feather is in clear view.

Step 4: Use the microscope’s objective lenses to magnify the feather. The lower the magnification, the more of the feather you will be able to see at once. Higher magnifications will allow you to see the details of the feather more clearly.

Step 5: Observe the feather carefully, noting any details you can see. You may want to take notes or draw what you see to help you remember what you observed.

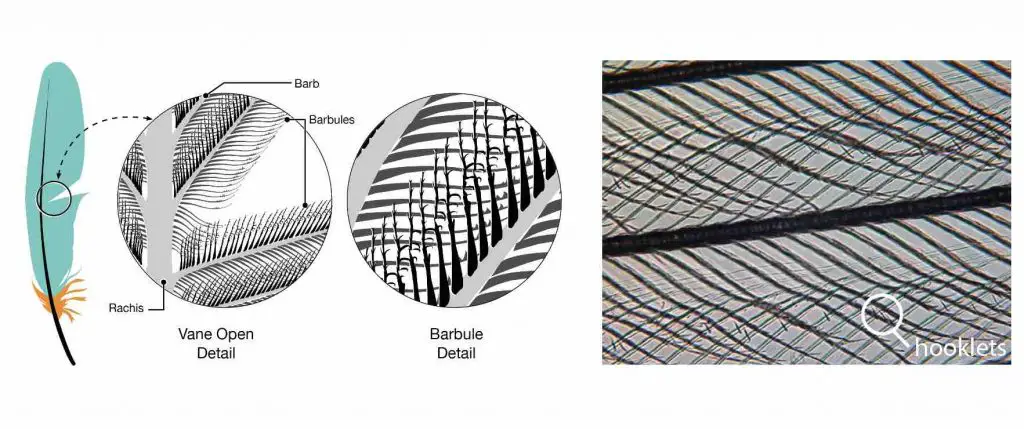

What will you see

[In this image] Left: Zoom in step-by-step to see the structure of Pennaceous feathers. Right: A real microscopic image showing these microscopic hooklets on the barbules that interlock to form a wind and waterproof barrier that allows birds to fly and stay dry.

Image source: Cornell Lab of Ornithology; Dove and Koch: Forensic Feather Identification

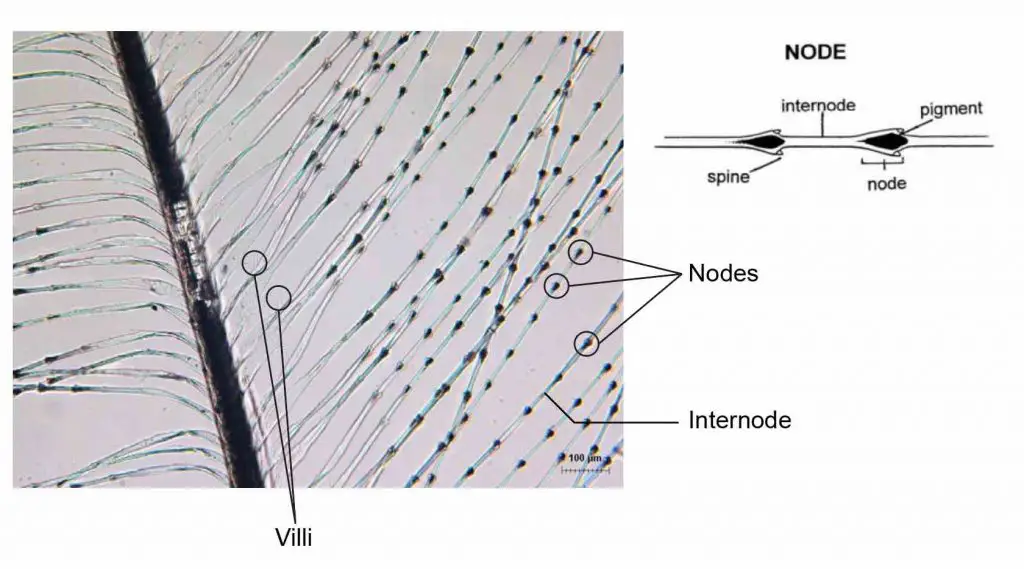

[In this image] When you get very close, you may find some feathers having these nodes containing pigments on their barbules. You can also see a very tiny spike, called villus (purple: villi) near the base of each barbule.

Image source: Dove and Koch: Forensic Feather Identification

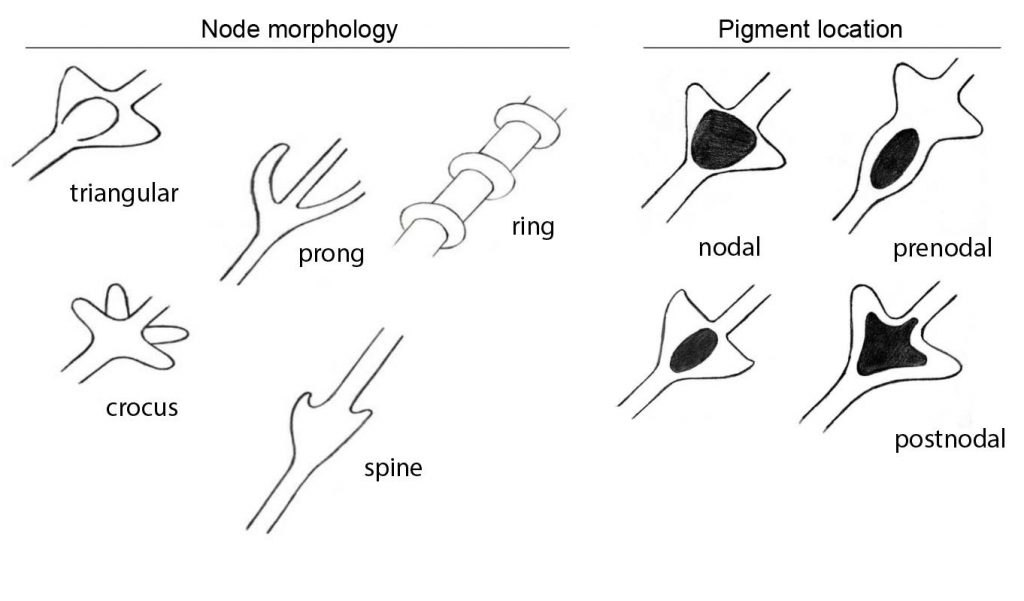

[In this image] By examining the node morphology, pigment location, and pigment distribution in barbules, bird experts can tell the potential owners of a lost feather.

Image source: Dove and Koch: Forensic Feather Identification

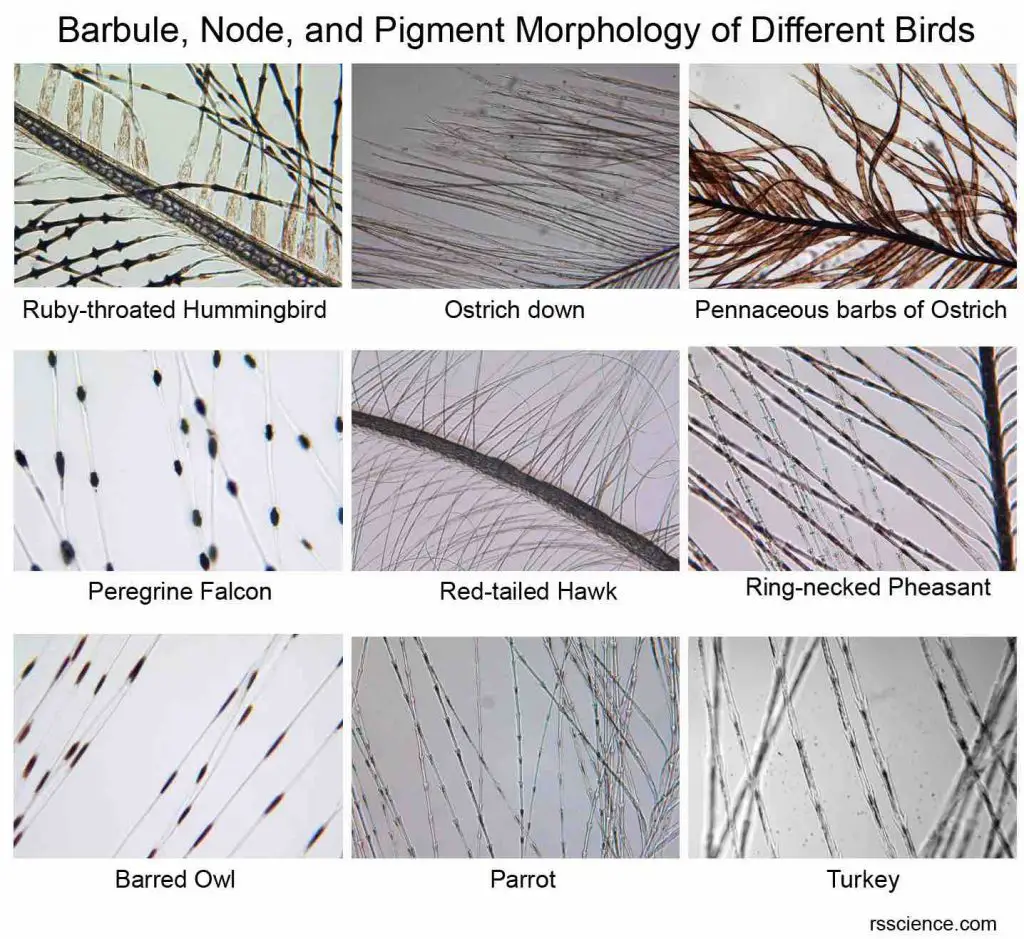

[In this image] A collection of microscopic images of different birds’ feathers (i.e., hummingbird, ostrich, falcon, hawk, pheasant, owl, parrot, and turkey) showing the diversity in barbule, node, and pigment morphology.

Image source: modified from Dove and Koch: Forensic Feather Identification

What to look for?

Take a flight feather and a down feather.

Try to compare flight feathers and downy feathers. One is used to make the wing, while the other keeps the birds warm. How is each feather designed to do its job?

Note: The flight feather has a central shaft with fibers branching off it. Look closer, and you’ll see that these branches, called barbs, have even smaller branches themselves, known as barbules. You may be able to see that the barbules have hooks that zip them all together to make the feather a single, streamlined surface.

The barbs on down feathers poke out in all directions, so the feather makes a ball of fluff – ideal for keeping warm, but not good for flying!

Can you identify what is pennaceous and what is a plumulaceous region?

Note: Pennaceous feathers are stiff and mostly flat. Plumulaceous regions are more fluffy.

[In this image] The Pennaceous and Plumulaceous regions of different feathers.

Try this Feather ID tool from the Forensics Laboratory of U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

[In this image] After examining the feathers, you can save them in your collection.

Image source: Deviant art

Where did the feathers come from?

If you like dinosaurs, you probably already know that the dinosaurs are very likely to be the ancestors of birds. Additionally, paleontologists have discovered that dinosaurs were the first animals to evolve feathers for covering their bodies.

In 1996, a fossil of a small dinosaur was found in China and named Sinosauropteryx, which means “Chinese dragon wing bird.” Paleontologists determined that Sinosauropteryx was covered in a coat of very basic, filament-like feathers, making it the first non-bird dinosaur with evidence of feathers.

[In this image] Sinosauropteryx fossil (125-million-year-old). You can see the “feathers” on its back.

Image source: wiki

[In this image] Sinosauropteryx fossil also provides us the first clear evidence of dinosaur colors. Paleontologists found they had orange and white striped tails.

Artwork by Chuang Zhao and Lida Xing

Fun facts about feathers

The longest feathers

In general, the longest feathers are grown by the Reeve’s pheasant, which lives in China’s forests. Males of these rare birds grow tail feathers that are 8 feet long!

Based on the Guinness World Records, the longest feathers grown by any bird were recorded in 1972 on a Yokohama chicken, whose tail covert measured 10.6 m (34 ft 9.5 in).

How many feathers a bird has?

Small songbirds have between 1,500 and 3,000 feathers, while eagles and birds of prey have 5,000 to 8,000 feathers. Swans have the most feathers, with as many as 25,000. On the other hand, hummingbirds have the fewest feathers, with only 1,000. Penguins have perhaps the densest (warmest) feather coat, with about 100 feathers per square inch.

Feathers can be heavier than a bird’s skeleton

That’s particularly true for birds that fly, which have lightweight (mostly hollow) bones to help them stay airborne. In some species, a bird’s skeleton makes up only 5% of its total body weight, meaning that its feathers account for a significant portion of the remainder.

Summary

1. A feather is a light, strong structure that grows on the skin of birds. The feathers on a bird serve several functions, including flight, insulation, waterproofing, display, intimidation, and camouflage.

2. The structure of a primary flight feather consists of a calamus, rachis, barb, barbule, pennaceous barbs, and plumulaceous barbs. The calamus extends into a central rachis, which branches into barbs and then into barbules with small hooks that interlock with adjacent barbules.

3. A down feather is made of mainly plumulaceous parts.

4. The feathers are made of a protein called keratin, which is also found in hair and nails in humans.

5. Seven types of feathers that are located on different parts of a bird’s body: wing feathers, tail feathers, contour feathers, semiplume feathers, down, filoplume, and bristle.

6. Some feathers have nodes containing pigments on their barbules. By analyzing the node morphology, pigment location, and pigment distribution in barbules, bird experts can tell the potential owners of a lost feather.

7. paleontologists have discovered that dinosaurs were the first animals to evolve feathers for covering their bodies.

References

“Feather Atlas” – an image database dedicated to the identification and study of the flight feathers of North American birds. The feathers illustrated are from the curated collection of the National Fish and Wildlife Forensics Laboratory.

“Interactive Learning – All About Feathers” from Bird Academy