This article covers

What is a planarian? A quick overview

Planaria or Planarians (singular: Planarian) are also called “cross-eyed worms”. They are a group of tiny flatworms belonging to the phylum of Platyhelminthes. They are free-living organisms and widely distributed in all kinds of freshwater habits.

[In this image] Planarian, a tiny flatworm, viewed under a microscope.

Photo credit: Sinhya / Getty Images

Planaria are small, measuring around 3 to 15 mm (0.1 to 0.6 inches), so they are easy to miss. However, planaria will possibly be the weirdest worm that you have ever seen. They have a soft, leaf-shaped body covered by tiny hairs (cilia). Their spade-shaped head has two eyes (sometimes, cross-eyes).

[In this image] A Planarian with an arrow-like head with two cross-eyes.

Photo credit: Royal BC Museum

Perhaps the weirdest thing is when a planarian is cut into pieces; each piece has the ability to regenerate into a fully formed worm. Let’s say you cut a planarian into 5 pieces. It will regrow into 5 different planaria. Their unusual traits make them widely studied in the scientific community.

[In this image] Left: A Planarian is cut into pieces. Right: A fragment regrows a new head and tail by day 12.

Photo credit: Josh Cassidy/KQED

In this article, you will learn the anatomy and behaviors of these amazing animals. Then, we will go into detail about their remarkable regenerative capability. I will show you several interesting scientific findings of the planarian, including a planarian regenerated to have “THREE heads”!

Classification of planarian – the phylum Platyhelminthes

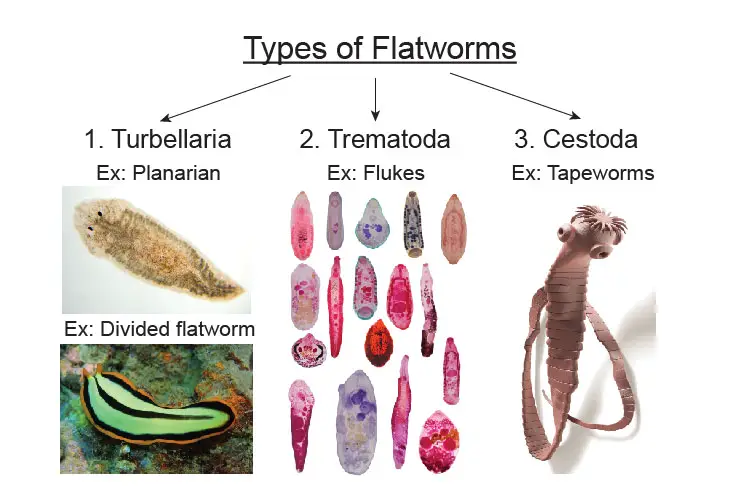

Planarian is a general term that includes many flatworms under the traditional class of Turbellaria. Turbellaria is one of three branches under the phylum of Platyhelminthes. Most Turbellaria are free-living flatworms. Some species of Turbellaria are parasitic, meaning that they obtain nourishment from the body of another living animal. Generally, we won’t call these parasitic ones Planaria.

[In this image] The phylum of Platyhelminthes.

The phylum Platyhelminthes includes flatworms. “Platy” means flat and “helminth” means worm. They can be divided into three major categories: (1) Turbellaria: free-living flatworms, like Planarian (in freshwater) and Divided flatworm (in marine); (2) Trematoda: parasitic flukes that Infect internal organs of a host. Ex. Schistosoma fluke causes Schistosomiasis – fluke’s eggs clog blood vessels of patients; (3) Cestoda: parasitic tapeworms, like pork and beef tapeworms, that have a snake-like long body and a head with suckers/hooks to attach to intestinal walls of a host.

Scientific classification

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Platyhelminthes

Class: Rhabditophora

Clade: Adiaphanida

Order: Tricladida

Family: Planariidae

(Reference: wiki)

What does a planarian look like?

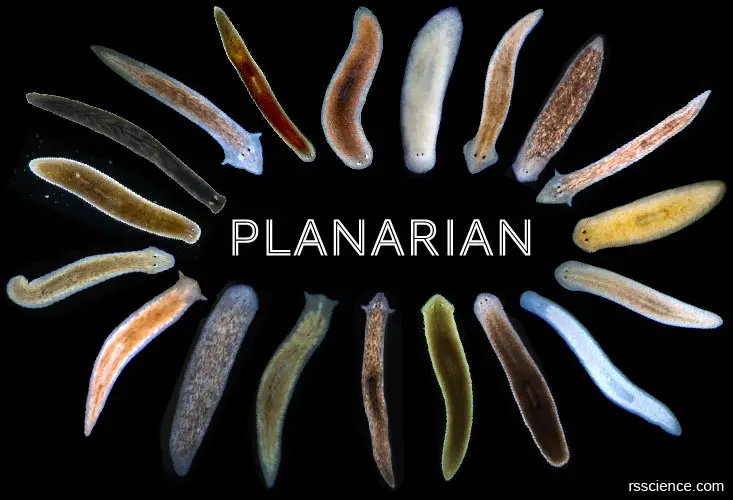

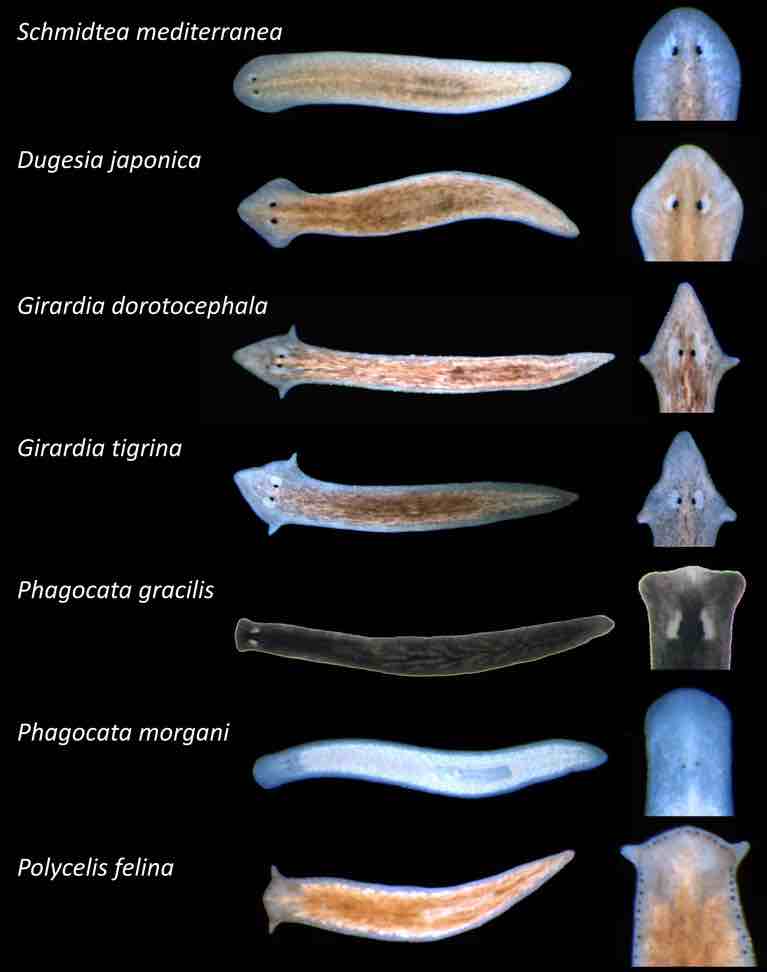

Planaria come in a wide range of colors, sizes, and head shapes. The most frequently used planarian in the classrooms and laboratories is the brownish Girardia tigrina. Other common species used are the blackish Planaria maculata and Girardia dorotocephala. Recently, Schmidtea mediterranea also becomes a popular model organism for molecular biological and genomic research.

[In this image] Planarian identification key. Here are several species of planaria studied in the laboratory of Wendy Scott Beane at Western Michigan University. The planarian species are distinguishable by their head shapes and body pigmentation.

Photo credit: The Beane lab

[In this image] Rhabdocoela is another kind of flatworm that is often confused with planarian.

Rhabdocoels are also free-living organisms with a similar size/color to white planaria. However, when compared side by side, the differences become clear – the shape of the head. A planarian usually has a triangular head and a Rhabdocoela has a rounded head.

Photo source: fishlab

Where can I find planarians?

Planaria are common in many parts of the world. Most planaria live in freshwater ponds and rivers, usually under rocks or water plants. Some marine species live in saltwater. Some species are terrestrial and are found under logs, in or on the soil, and on plants in humid areas.

Planaria can not tolerate polluted water. For this reason, they are often studied as bio-indicators in a watery ecosystem.

[In this image] A terrestrial planarian (Obama nungara) lives in moss.

Photo source: wiki

[In this image] A freshwater planarian (Dugesia gonocephala) moving on a leaf.

Photo source: Jan Hamrsky

The body structure of planarian

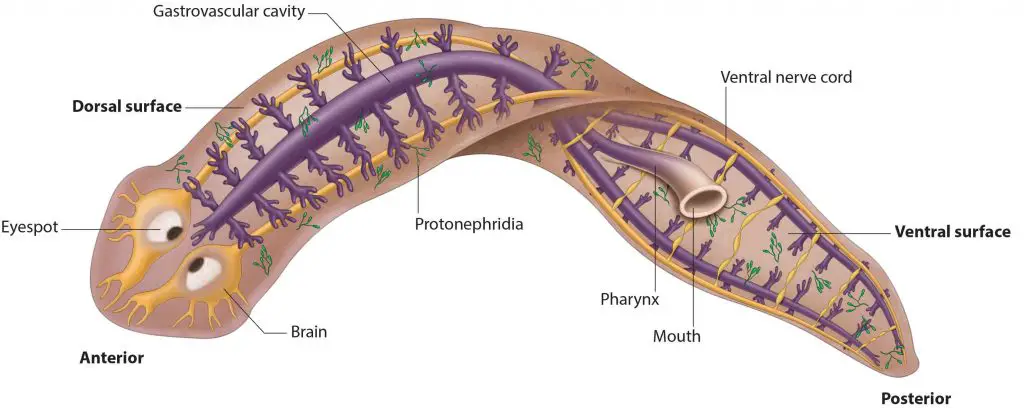

[In this image] The anatomy of a planarian showing its digestive (purple), excretory (green), and nervous (yellow) systems.

Photo source: cuttingclass

Size

The length of a planarian is usually about 3 to 15 mm (0.1 to 0.6 inches); some can grow up to 30 cm (about 1 foot) long.

[In this image] Some terrestrial planaria are much longer than the ones that live in the water.

Photo source: The Wildlife Trusts

Color

Tropical species are often brightly colored. Members of the North American genus Dugesia are black, gray, or brown.

[In this image] A brown speckled planarian (Dugesia tigrine).

Photo source: Marc Perkins

Body

The body of Planaria is soft (lack of skeleton) and leaf-shaped (bilateral symmetry). The bottom surface is covered by tiny hairs, called cilia. The spade-shaped head has two eyes and sometimes auricles. The tail is pointed.

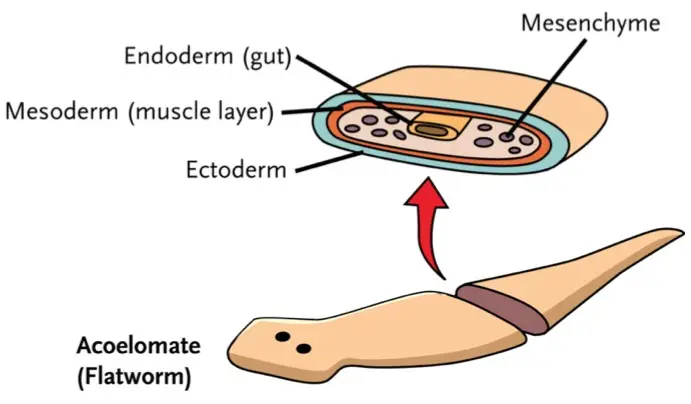

Planaria have three germ cell layers (i.e., ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm), which are the same as humans. They have a solid body with no body cavity (referred to as acoelomate).

[In this image] Planarian body plan: Ectoderm (outside), Endoderm (inside), and Mesoderm (middle layer of tissue between the ectoderm and the endoderm).

Photo credit: ck-12

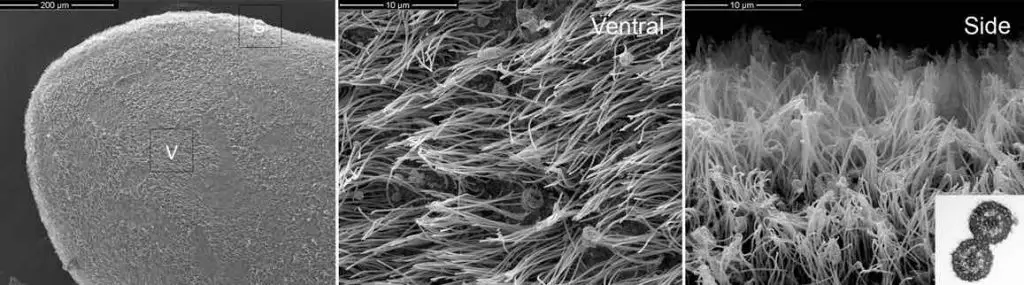

Skin, Muscle, and Cilia

The skin (dermis) of planaria is covered by cilia (tiny hairs) and gel-like mucus. Planaria move by beating their cilia, allowing them to glide along on the mucus film. Some also move by undulations (moving smoothly up and down) of the whole body by the contractions of muscles beneath the skin.

[In this image] Electron microscopy of S. mediterranea cilia.

The entire ventral (belly) surface of the planarian body consists of a highly ciliated epithelium.

Photo source: Semantic scholar

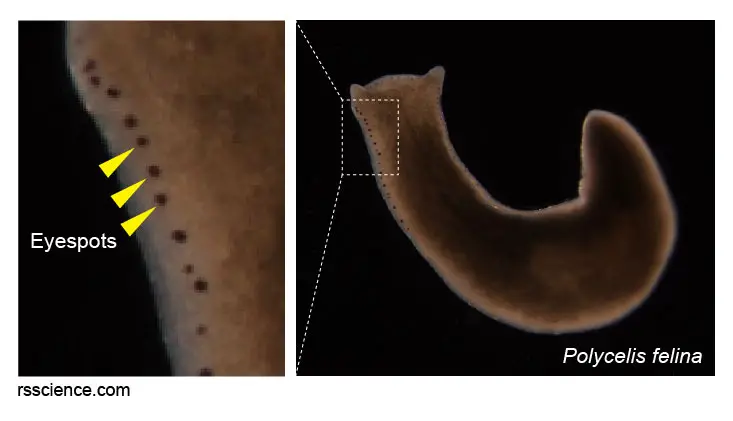

Eyes

Some planarian species have two eyespots (also known as ocelli). It is funny since it looks like the planarian has cross-eyes. However, some species may have several eye spots. For example, one species, Polycelis felina, even has over 20 eyes.

[In this image] Polycelis felina can have more than 20 eyespots on its head.

Modified from eaufrance

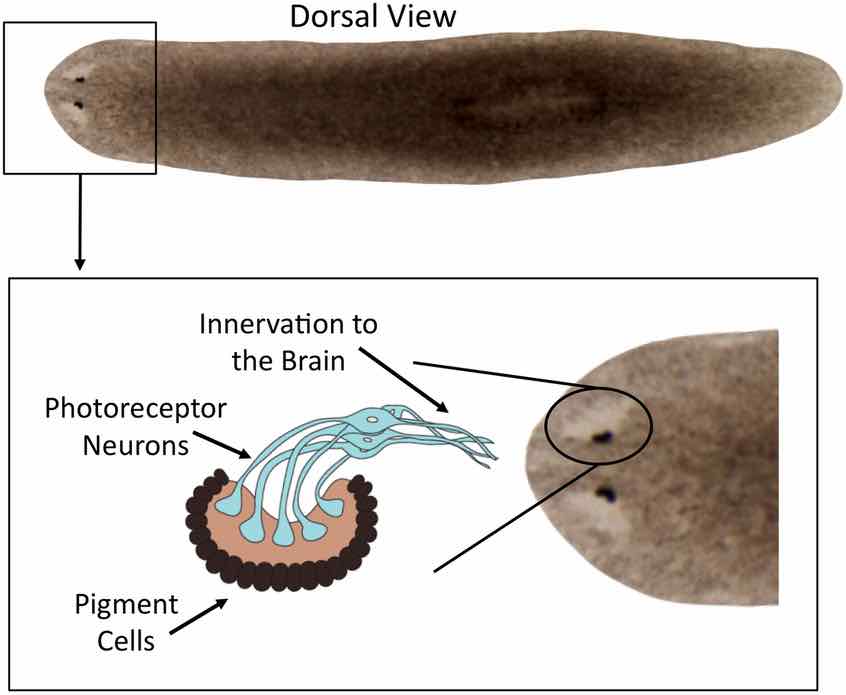

These eyespots consist of photoreceptor cells that can detect the intensity of light. Planaria use their eyes to move away from bright light sources.

[In this image] The dark portions are pigment-filled cells that partially surround the photosensory neurons, shading them from one side (thus allowing them to detect the direction of light without a lens, retina, or movable eye).

Photo source: Paskin T.R., et. al., PLoS One, 2014

Auricles

Some planaria have two ear-like structures, called auricles, on their heads. Auricles can’t hear the sound but can sense touch.

[In this image] A brown speckled planarian (Dugesia tigrine). You can see two eyespots and auricles on its head.

Photo source: Marc Perkins

Planarian’s organ systems

Planaria are small, but not simple. A planarian with a body 6 mm long contains approximately 6×105 (0.6 million) cells. They have several unique organ systems which function like ours.

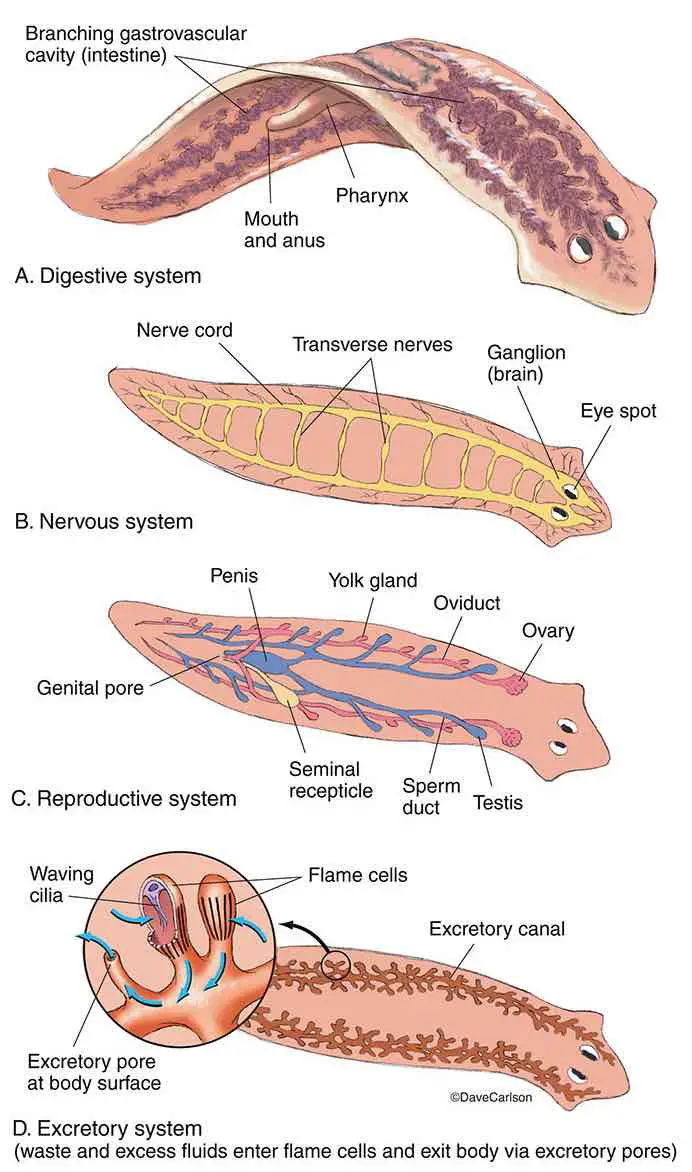

[In this image] Planaria have four organ systems: Digestive, Nervous, Reproduction, and Excretory systems.

Photo source: Carlson stock art

Digestive system

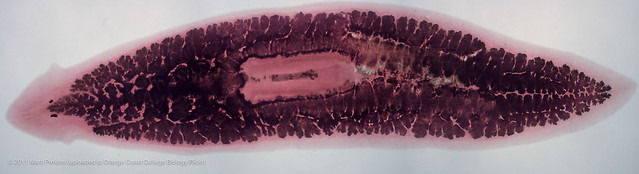

Planaria have a single-opening digestive tract, which consists of a mouth, pharynx, and gastrovascular cavity. The mouth of the planarian doesn’t stay close to its eyes. Instead, its mouth is located in the center (sometimes, even closer to the tail) of the underside of the body. The pharynx connects the mouth to the gastrovascular cavity, which branches throughout the body.

[In this image] In this anatomy of a planarian, you can see the pharynx protruding from the mouth opening.

Small invertebrates or the remains of dead animals are taken into the mouth by the muscular pharynx. The food is then digested in the highly branched gastrovascular cavity. Tricladida planaria (shown here) has one anterior branch and two posterior branches.

Photo credit: zoology

[In this image] A planarian feeds by protruding its pharynx to suck up the food.

Photo source: Marc Perkins

The Planarian’s digestive tract has only one opening. So, its mouth also serves as its anus to expel undigested food debris.

[In this image] A whole preserved planarian after the gastrovascular cavity (gut) has been filled with ink. In the center of the body is the pharynx, a long tubular structure that is extended from the body to feed.

Photo source: Marc Perkins

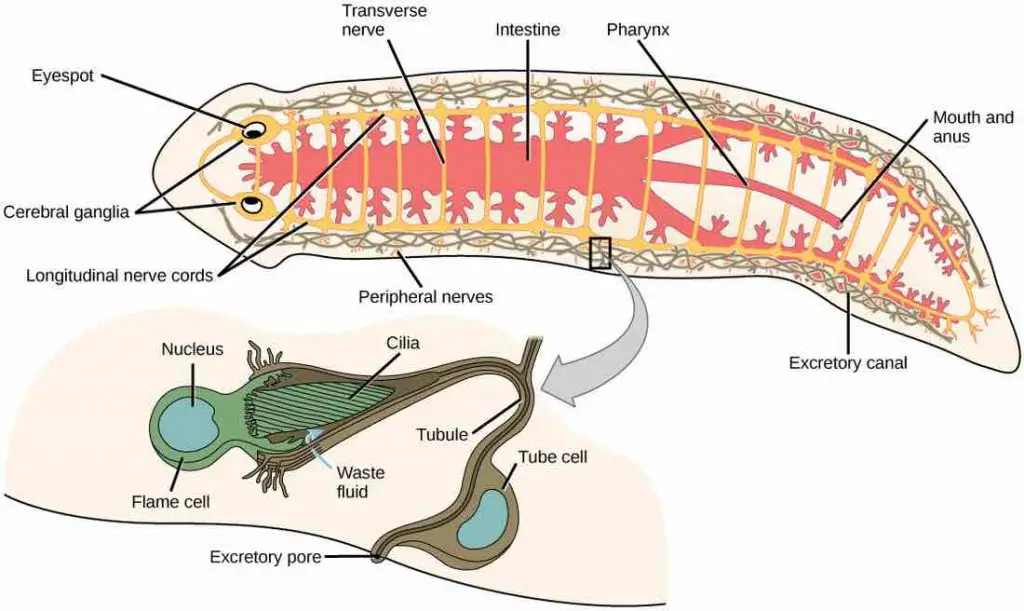

Excretory system

Surprisingly, planarian has a system to perform the excretory function like our kidney.

This primitive excretory system consists of tubules connected to a highly-branched duct network. These tubules have pores located all along the sides of the body. The waste will be secreted through these pores.

These cells forming the tubules are called flame cells (or protonephridia). Flame cells were named because they have a cluster of cilia that looks like a flickering flame when viewed under the microscope.

Flame cells function like nephrons in our kidney, removing waste materials through filtration. The cilia propel waste matter down the tubules and out of the body through excretory pores that open on the body surface. Cilia also draw water from the interstitial fluid, allowing for filtration. After excretion, any useful nutrients will be reabsorbed by the cells.

[In this image] Planarian’s excretory system is made up of tubules connected to excretory pores on both sides of the body. Flame cells use their cilia to propel waste down the tubules formed by tube cells.

Photo source: Flatwormz

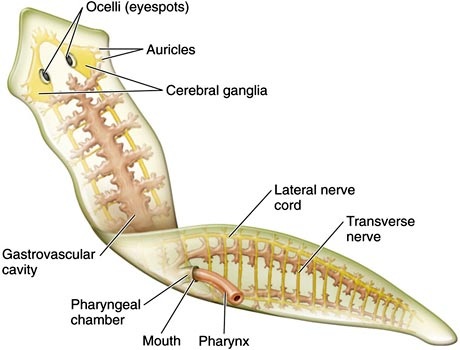

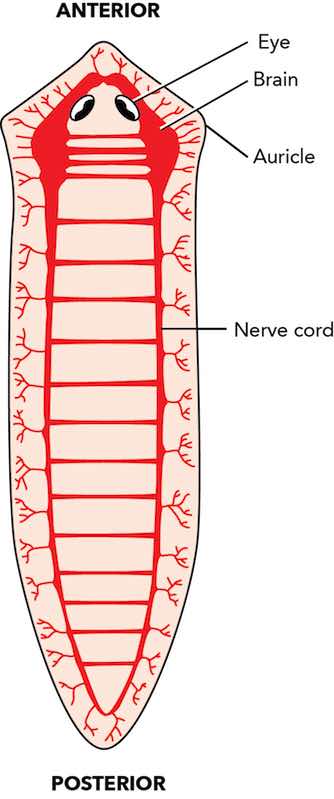

Nervous system

Planarian’s nervous system consists of two interconnected nerve cords running the length of the body. They also have two large ganglia (like a primitive brain) and eyespots at the head part. These nerve cords connect the ganglia and photosensory or chemosensory cells together.

Ganglia (singular = ganglion) in the head region relay messages from the sensory cells down the nerve cords to the rest of the body. The nerve cords can control muscles in the body that allow the worms to move or eat.

[In this image] Planarian’s nervous system.

The cerebral ganglia, a bi-lobed mass of nerve tissue, is sometimes called the planarian “brain”. From the ganglia, two nerve cords extend all the way to the tail. Many transverse nerves connect between the two nerve cords, making the nerve system look like a ladder. With this nerve system, the planarian is able to move in a coordinated manner.

Photo source: Byron Inouye

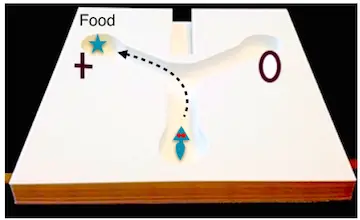

Planaria can sense and respond to at least three forms of stimuli:

- Light: the eyespots can detect light and allow the flatworms to react to it.

- Chemicals: the pits on the side of their head regions allow the worms to smell.

- Touch: the auricles on either side of the head region can sense touch and allow the worms to respond.

Scientists even found that a planarian has a simple learning capability. By nature, a planarian moves away from light. However, after being trained with food, it can learn to stay in the light.

[In this image] Planarians respond well to food as positive reinforcement.

Photo source: Study.com

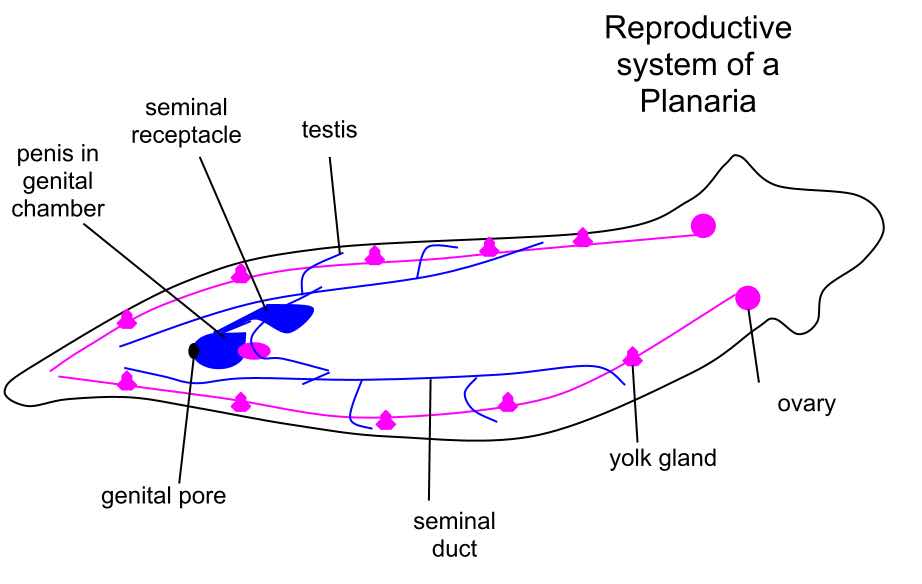

Reproduction system

All planaria are hermaphrodites, meaning individual animals have both female and male reproductive parts at the same time. Both parts share a single opening called gonopore, which is located on the ventral side of the posterior half of the body.

[In this image] Planarian reproductive system.

Photo source: wiki

Reproduction of planarian

Planaria can reproduce both asexually and sexually. Asexual reproduction is common through fission. During fission, planaria basically attach themselves by their tail and then stretch until they pull themselves apart and divide into two pieces! The head fragment will regenerate a new tail, and the tail fragment will regenerate a new head. Two weeks later, you will have two worms instead of just one – both genetically identical!

Sexually, planarians are hermaphrodites, possessing both testicles and ovaries. However, sexual reproduction requires two individuals. Thus, one of their gametes will combine with the gamete of another planarian. Eggs develop inside the body and are shed in capsules. A few weeks later, the eggs hatch and grow into new worms.

[In this image] A planarian egg capsule on a stalk.

Photo source: Jan Hamrsky

Planarians’ behavior and Q&A

How does a planarian breathe?

Planaria have neither a circulatory nor respiratory system. Therefore, they breathe by diffusion. This necessarily limits the thickness of the body of planaria, constraining them to be “flat” worms.

How does a planarian move?

Planaria move across a surface using cilia on their ventral (meaning belly) surface. They can secrete a film of gel-like mucus to serve as a lubricant. They also move by contracting their muscles to swim with an undulating motion or creep like slugs. These muscles are controlled and coordinated by the nerve cords.

[In this video] See how the planaria move under the microscope.

What does a planarian eat?

The choices of diets for planaria could be divided into two groups. A group of planaria feast on waste. The remains of plants and animals and even poop – are all tasty meals for these planaria.

On the other hand, some planaria are successful predators and hunt for worms, snails, and small arthropods, such as daphnia, isopods, and baby shrimps.

Planarian eats by sucking up food (could be live or dead small animals) with its muscular mouth. Food passes from the mouth through the pharynx into the intestines where it is digested by digestive enzymes. Then its nutrients diffuse to the rest of the planarian through the branches of the gastrovascular cavity.

[In this video] See how the planaria eat under the microscope.

Some species can secrete digestive enzymes from the mouth to digest the food externally. Then, the planarian sucks up digested food into its body.

Are planarians harmful to humans?

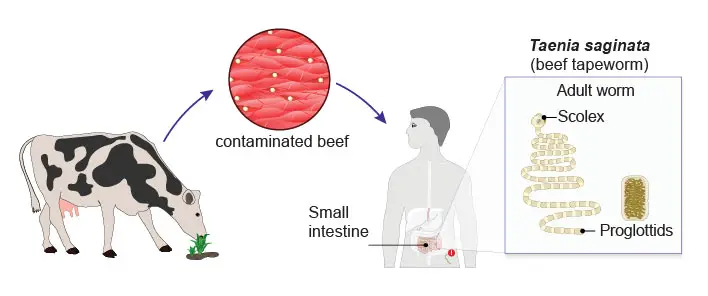

Free-living planaria (including most members in the class Turbellaria) are not parasites and not harmful to humans. However, planaria’s cousins in the class of trematodes (flukes) and cestodes (tapeworms) could be internal parasites. Some of these parasitic worms can cause serious human diseases including schistosomiasis (by blood flukes) and Taeniasis (by Taenia saginata = beef tapeworm or Taenia solium = pork tapeworm).

[In this image] Tapeworm (Taenia sp.) infections (Taeniasis) occur when humans consume raw or undercooked infected meat.

Planarians’ super regenerative powers

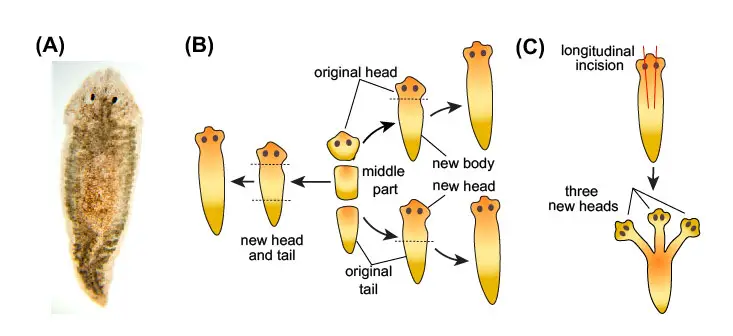

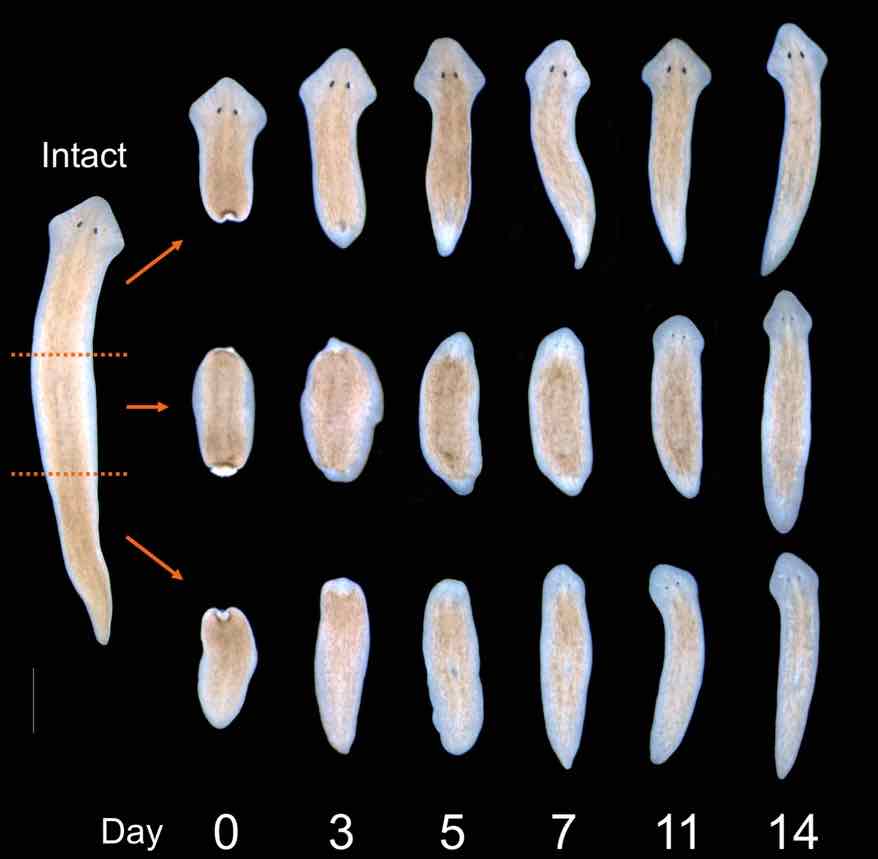

Planaria are remarkable in that they can regenerate an entire worm from just a tiny fragment of the original. For example, a planarian cut into three pieces (head, body, tail) will regenerate into three separate individuals. You can even create a three-headed planarian if you make two incisions on its head.

[In this image] (A) The most frequently used planarian in high school and first-year college laboratories is the brownish Girardia tigrina. (B) A planarian cut into three pieces (head, body, tail) will regenerate into three separate individuals. (C) Two incisions on a planarian’s head can regenerate into a three-headed planarian.

Planaria can do this remarkable feat because roughly 25% of their body is made up of adult stem cells, which are able to regenerate all tissues. Furthermore, these new cells know how to rebuild the body the right way – growing only one head instead of two.

[In this image] The regeneration of the planarian was accomplished in just two weeks.

Photo credit: The Beane lab

[In this video] A Time-lapse recording of the planaria regeneration process.

In the laboratory, scientists utilize planaria as a model organism to further our understanding the regeneration. The ultimate goal will be regenerative medicine. If we can figure out how to copy the planarian’s regenerative powers to human patients, he/she may cure themselves by replacing damaged organs or lost limbs.

Check the post ” planarian’s super regenerative powers” to learn more. We will show you how scientists study this amazing process – at the levels of cell biology and gene functions.

[In this image] When scientists removed a critical gene from a planarian, it confused and regenerated into a multi-headed planarian.

Photo source: Peter Reddien

You can also read our article “What is an induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)?” to learn the most promising biotechnology that may one day make regenerative medicine happen!

How to obtain planarians for your microscopic project

Planaria can be found in all kinds of unpolluted freshwater habits. Since they like to move away from bright sunlight, they are typically found under rocks, logs, and debris in streams, ponds, and springs. Try to turn over a rock to see if you can find one. You can use a drop to pick up the planaria into a tube or a dish.

[In this image] Many planaria reside on the underside of a rock.

Planaria are considered a pest by the majority of aquarists. These flatworms can quickly multiply in number and cause problems in their fish tanks. For this reason, if you can spot planaria in your friend’s tank or in an aquarium shop, you probably can get them for free.

[In this image] Planaria grow in number in this fish tank and slide their way over the aquarium glass.

Photo source: fishlab

[In this image] Planaria Trap.

For a fish tank having a serious problem with worms, aquarists may place planaria traps to capture and remove planaria – by baiting them with raw chicken!

Photo source: Amazon

[In this image] Planaria are small but visible to the naked eye.

Photo credit: The Beane lab

[In this image] You can carefully move planaria with a liquid dropper.

Photo source: HHMI/BioInteractive

Summary

1. Planaria are a group of free-living flatworms. Unlike other parasitic worms in the phylum of Platyhelminthes, Planaria are generally harmless to humans.

2. Planaria have several primitive organ systems – Digestive, Nervous, Reproduction, and Excretory systems.

3. Planaria are characterized by having two eyespots on the heads. The eyespots can help planaria sense and respond to light.

4. Planaria have the primitive brain and nervous system.

5. Planaria are remarkable in that they can regenerate an entire worm from just a tiny fragment of the original.

6. Scientists are trying to figure out how this regeneration happens. Hopefully, one day we can learn from planaria to replace lost organs or limbs.

References

“Planaria: adorable flatworms”

“Hands-On Classroom Activities for Exploring Regeneration and Stem Cell Biology with Planarians”

“Types or States? Cellular Dynamics and Regenerative Potential”